Being an unregenerate fan of pulp literature, I was asked to review some new releases of Sax Rohmer’s exhilarating Fu Manchu series. In the end the journal - an American academic effort - decided not to use my piece. Exactly why remains a mystery, but I suspect my take on the evil doctor wasn’t quite politically correct enough. You decide.

The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu

The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu

Sax Rohmer

London: Titan Books, 2012

9780857686039

9780857686046

$9.95

The Yellow Peril of Dr. Fu Manchu

“Imagine a person, tall, lean, and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government – which, however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.”

Thus did Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward – better known as Sax Rohmer – describe his most popular and successful creation. In the insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu, Rohmer created a fictional character that became a modern archetype, a popular icon of the same stature as Sherlock Holmes, James Bond, and Tarzan, spawning dozens of books, films, radio and television shows, comic books, and not a few imitations. The evil Asiatic genius first appeared in 1912, his adventures serialized in The Story Teller; hence the episodic character of The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu, his hardback debut, published in 1914. But both Rohmer and the Doctor had their most successful years in the 1920s and ‘30s. It was then that Rohmer was persuaded to return to his diabolical creation, after trying to finish him off, as his older contemporary Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had tried with Sherlock Holmes. Both Doyle and Rohmer were prolific writers and both believed their best work lay elsewhere. Their reading public disagreed, and were proved right, to both Doyle’s and Rohmer’s financial profit. Rohmer was for some years one of the highest paid writers in England, if not the world, with tens of millions of copies of his books in print, and in his last years is said to have sold the film, television, and radio rights to his malevolent Doctor for some several million dollars. Rohmer died in 1959 at seventy-six and over the years a bad business sense and a penchant forMonte Carlo sadly siphoned off quite a lot of his cash.

Fu Manchu has been played on the silver screen by Warner Oland, Boris Karloff, Christopher Lee, Peter Sellers, and even Nicholas Cage. Karloff’s deliriously lurid The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), with its racially edgy dialogue and de trop sadism (enjoyed by Myrna Loy as the Doctor’s evil daughter), remains a classic. Ian Fleming’s evil Chinese Dr. No – the first Bond baddie in the film series - is a sleek, rocket-age version of Rohmer’s arch-villain, and Iron Man’s evil Asian nemesis, the Mandarin, is Marvel Comics’ nod to Rohmer’s dastardly Chinamen. In fact, when you think of it, there have been quite a few diabolical villains from old Cathay intent on terrorizing the West, and if you trace back their lineage, most of them have their roots in Rohmer’s evil genius.

Yet, mention Sax Rohmer today, and you may just get a nod. Fu Manchu still rings a bell, but the moustache first comes to mind, an accoutrement added in the films, although Rohmer’s original was clean-shaven. But if anything, the only evil Rohmer’s creation troubles us with now is his creator’s so-called racism. Back in the days before political correctness, Rohmer admitted that when he first conceived the idea of Fu Manchu, the Boxer Rebellion (1898-1901) was still in people’s minds and the threat of a “yellow peril” still seemed possible. “Conditions for launching a Chinese villain on the market were ideal,” he told his biographer Cay Van Ash, much as today, when more than one blockbuster thriller capitalizes on the fear of an imminent terrorist threat. By our standards, Rohmer’s Fu Manchu books – there are thirteen in all with a posthumous collection of short stories, and Titan Books heroically promises to release every one – reek of racial slurs, or at least of the intention to profit by vulgar stereotypes and misconceptions. Rohmer’s heroes, the steadfastly British Nayland Smith, a Burmese police commissioner with extraordinary legal powers, and the stories’ narrator, the reflective Dr. Petrie, named after the famed Egyptologist, Flinders Petrie (the pair were clearly modelled on Holmes and Watson), save the “white race” from extinction regularly. As Smith tells Petrie, there was an “awakening in the East,” and “millions only wait their leader” to initiate another invasion of the “yellow hordes.” That leader, of course, is Fu Manchu, who is the agent of the mysterious Si-Fan, a Chinese secret organization in control of Tong societies around the world, and whose aim is to undermine the West through drugs, white slavery, and a wave of assassinations. The plots of the first two books – The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu essentially carries on from the Doctor’s debut – center around the efforts of Smith and Petrie to foil Fu Manchu’s plan to eliminate all who would stand in his way, and their breathtaking and frequent escapes from their own doom at the hands of the Sinocentric “devil doctor.”

Yet I seriously doubt if Rohmer himself was racist, although we might accuse him of opportunism. “I made my name on Fu Manchu,” he said, “because I know nothing about the Chinese.” (His great love, in fact, was Egyptand the Middle East.) It’s doubtful if anything Rohmer wrote triggered any hate crimes and only the most fastidiously politically correct reader would find either of these magnificently entertaining thrillers offensive. If you can bracket “realism,” police procedure, and CSI for a few hours, plunge into Rohmer’s pulse-thumping prose and fin-de-siècle atmosphere, filled with the opium dens and foggy Limehouse docks of a long lostLondon. You’ll be delighted, even if your guilty conscience cringes at the mention of “yellow devils” and the “fiendish Asiatic race.”

The idea of a “yellow peril,” a threat to the white race from a growing Asian geo-political power, seems to have arisen in the 1890s in German fears about Japanese expansion. But the term earned pulp currency in 1898 in the weird fiction writer M. P. Shiel’s serial The Empress of the Earth, later published in novel form as The Yellow Danger. Others less talented picked up the idea, but it wasn’t limited to writers of pulpy trash. Jack London’s The Unparalleled Invasion (1910) uses it, and it also forms the backdrop to Andrei Bely’s hallucinatory modernist novel Petersburg (1913), where it is called the “Mongol Peril” – Russians were afraid of the East, too - and it runs through the Polish avant-gardist Witkacy’s unclassifiable work Insatiability (1927), where it is presented as a Chinese takeover ofEurope. The central idea was thatAsia was breeding a new force, capable of overthrowing Western dominance, and that we should take steps to defeat it. Rohmer took this sensational theme and ran with it.

But fears of an Asian invader could not have secured Rohmer’s success alone. What carries both of these immensely enjoyable books is Rohmer’s ability to interweave his fantastic, bracingly unbelievable plots with the arcane knowledge he picked up over the years, an erudition that Fu Manchu of course puts to diabolical use. Rather than the crude bombs and vulgar bullets of other criminals, Fu Manchu employs Dacoits and Thugees (Indian bandits and assassins), drugs (mostly hashish and opium), pythons, spiders and other poisonous insects, poisonous mushrooms (occasionally an hallucinogenic one), germ warfare, and even a marmoset, in his fiendish designs.

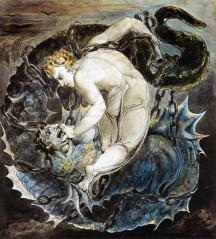

Rohmer himself was self-taught and a keen student of the occult and esoteric; it is said that he belonged to the celebrated Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, of which Aleister Crowley and W.B Yeats were members, but this may be apocryphal. Whether he did or not, he did some research into magic – his one work of non-fiction, The Romance of Sorcery (1915), is a product of it – and although it is sometimes only hinted at, an air of the supernatural breathes throughout all his work. It is this mixture of the arcane, the outré, and the exotic, with an adrenaline fuelled narrative, that gives the Fu Manchu books their unmistakable appeal. And if in Fu Manchu Rohmer encapsulated western fears of an Asian threat, in the character of the Arab slave girl Kâramanéh, forced to do the evil Doctor’s bidding, he embodied –literally – all of its exotic allure. Dr. Petrie falls in love with Kâramanéh, with her “eyes like the velvet darkness of the East,” and his attentions are reciprocated. If we want to get semiotic about it, we could say that in Fu Manchu and Kâramanéh, Rohmer personalizes the West’s millennial fear of the mysterious East as well as its irresistible attraction, the seductive Other we at once pursue and repel, an addictive relationship going back at least to The Arabian Nights and Gérard de Nerval’s Journey to the Orient. I’m sure there’s an academic thesis about this somewhere, but it would be thin fare next to Rohmer’s rollicking tales.

Rohmer himself had an unusual life and he only came to fiction after unsuccessful attempts at earning an honest living as a civil servant, clerk, and reporter. Rohmer was born in Birminghamin England’s West Midlandsin 1883 to Irish immigrant parents. His father was an underpaid and overworked office clerk and his mother a highly-strung woman who slowly sank into alcoholism. Rohmer spent a great deal of his childhood alone and unattended; one possible product of his feral youth was a somnambulism which had him on occasion throttling his father and trying to jump out a window. For a time he wrote songs and comedy sketches for London music hall comedians, and in 1911 he ghost wrote the autobiography of Little Tich, one of the most famous. Although he never made it to China, Rohmer did travel in Egyptand the Middle East. One of his most effective novels, Brood of the Witch Queen (1918), has a series of murders carried out via the dark magic of the fabled Book of Thoth. Rohmer also developed other central characters and based other series on them. There was Gaston Max, a Parisian detective, who debuted in The Yellow Claw (1915); Morris Klaw, the Dream Detective, a Jewish East End curio-seller who solves crimes via the Kabbalah; and Sumuru, a buxom super-villainess – Russ Meyer would have approved - who also made it to the big screen in The Million Eyes of Sumuru (1967) an obtainable cult-classic, and the sequel That Girl From Rio (1969), as well as Sumuru (2003).

Although the Boxer Rebellion may have primed the public for Fu Manchu, Rohmer claimed that the Doctor had a real life prototype. While working for a Fleet Street tabloid in 1911, Rohmer was assigned to write an article about the Chinese underworld ofLondon’s Limehouse, today a desirable “historical” location, but back then a dockside warren of crime, decadence, and danger. He had heard stories about a mysterious “Mr. King,” who was purported to be the mastermind behind Limehouse’s evil economy of drugs, sex, and gambling. Access to Mr. King was understandably limited, and he never met him, but Rohmer did manage a sighting. When a “tall, dignified Chinese, wearing a fur-collared overcoat,” stepped out of the car, Rohmer knew that he had seen Fu Manchu, whose “face was the living embodiment of Satan.” He was never sure whether the man he saw was Mr. King or not, but by then that hardly mattered.

In the later books, Fu Manchu’s objectives change, and the emphasis on the threat to the white race recedes. By the end he is fighting Communism, and is, if not a friend, at least a tactical ally with the West. Popular taste in evil Asians had also changed. Earl Derr Biggers’ amiable Chinese detective Charlie Chan appeared in 1925, Mr. Moto, John Marquand’s Japanese secret agent, turned up in 1935, and Hugh Wiley’s Mr. Wong, the San Francisco sleuth, in 1938. These stories too have been accused of racism, but at least the moan of contention surrounds a good guy. Enjoy.