A writer is always pleased to see reviews of his books, even bad ones, as they at least suggest that someone is reading his work. But when you come across a review that actually understands what you are trying to do - well, one can be practically overjoyed. Here is an excellent review of my book The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus that I recently came across trawling through the net.

Tag: Gary Lachman

Swedenborg and Electric Politics

Here’s an interview with me on Electric Politics about everyone’s favourite Swedish mystic.

Madame Blavatsky: The Mother of Modern Spirituality

Here’s the introduction to my new book, Madame Blavatsky: The Mother of Modern Spirituality, courtesy of my publishers Tarcher/Penguin. The book will be released in the US on October 25th, and a bit later in the UK. I hope the Madame approves.

The Yellow Peril of Dr. Fu Manchu

Being an unregenerate fan of pulp literature, I was asked to review some new releases of Sax Rohmer’s exhilarating Fu Manchu series. In the end the journal - an American academic effort - decided not to use my piece. Exactly why remains a mystery, but I suspect my take on the evil doctor wasn’t quite politically correct enough. You decide.

The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu

The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu

Sax Rohmer

London: Titan Books, 2012

9780857686039

9780857686046

$9.95

The Yellow Peril of Dr. Fu Manchu

“Imagine a person, tall, lean, and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government – which, however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.”

Thus did Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward – better known as Sax Rohmer – describe his most popular and successful creation. In the insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu, Rohmer created a fictional character that became a modern archetype, a popular icon of the same stature as Sherlock Holmes, James Bond, and Tarzan, spawning dozens of books, films, radio and television shows, comic books, and not a few imitations. The evil Asiatic genius first appeared in 1912, his adventures serialized in The Story Teller; hence the episodic character of The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu, his hardback debut, published in 1914. But both Rohmer and the Doctor had their most successful years in the 1920s and ‘30s. It was then that Rohmer was persuaded to return to his diabolical creation, after trying to finish him off, as his older contemporary Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had tried with Sherlock Holmes. Both Doyle and Rohmer were prolific writers and both believed their best work lay elsewhere. Their reading public disagreed, and were proved right, to both Doyle’s and Rohmer’s financial profit. Rohmer was for some years one of the highest paid writers in England, if not the world, with tens of millions of copies of his books in print, and in his last years is said to have sold the film, television, and radio rights to his malevolent Doctor for some several million dollars. Rohmer died in 1959 at seventy-six and over the years a bad business sense and a penchant forMonte Carlo sadly siphoned off quite a lot of his cash.

Fu Manchu has been played on the silver screen by Warner Oland, Boris Karloff, Christopher Lee, Peter Sellers, and even Nicholas Cage. Karloff’s deliriously lurid The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), with its racially edgy dialogue and de trop sadism (enjoyed by Myrna Loy as the Doctor’s evil daughter), remains a classic. Ian Fleming’s evil Chinese Dr. No – the first Bond baddie in the film series - is a sleek, rocket-age version of Rohmer’s arch-villain, and Iron Man’s evil Asian nemesis, the Mandarin, is Marvel Comics’ nod to Rohmer’s dastardly Chinamen. In fact, when you think of it, there have been quite a few diabolical villains from old Cathay intent on terrorizing the West, and if you trace back their lineage, most of them have their roots in Rohmer’s evil genius.

Yet, mention Sax Rohmer today, and you may just get a nod. Fu Manchu still rings a bell, but the moustache first comes to mind, an accoutrement added in the films, although Rohmer’s original was clean-shaven. But if anything, the only evil Rohmer’s creation troubles us with now is his creator’s so-called racism. Back in the days before political correctness, Rohmer admitted that when he first conceived the idea of Fu Manchu, the Boxer Rebellion (1898-1901) was still in people’s minds and the threat of a “yellow peril” still seemed possible. “Conditions for launching a Chinese villain on the market were ideal,” he told his biographer Cay Van Ash, much as today, when more than one blockbuster thriller capitalizes on the fear of an imminent terrorist threat. By our standards, Rohmer’s Fu Manchu books – there are thirteen in all with a posthumous collection of short stories, and Titan Books heroically promises to release every one – reek of racial slurs, or at least of the intention to profit by vulgar stereotypes and misconceptions. Rohmer’s heroes, the steadfastly British Nayland Smith, a Burmese police commissioner with extraordinary legal powers, and the stories’ narrator, the reflective Dr. Petrie, named after the famed Egyptologist, Flinders Petrie (the pair were clearly modelled on Holmes and Watson), save the “white race” from extinction regularly. As Smith tells Petrie, there was an “awakening in the East,” and “millions only wait their leader” to initiate another invasion of the “yellow hordes.” That leader, of course, is Fu Manchu, who is the agent of the mysterious Si-Fan, a Chinese secret organization in control of Tong societies around the world, and whose aim is to undermine the West through drugs, white slavery, and a wave of assassinations. The plots of the first two books – The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu essentially carries on from the Doctor’s debut – center around the efforts of Smith and Petrie to foil Fu Manchu’s plan to eliminate all who would stand in his way, and their breathtaking and frequent escapes from their own doom at the hands of the Sinocentric “devil doctor.”

Yet I seriously doubt if Rohmer himself was racist, although we might accuse him of opportunism. “I made my name on Fu Manchu,” he said, “because I know nothing about the Chinese.” (His great love, in fact, was Egyptand the Middle East.) It’s doubtful if anything Rohmer wrote triggered any hate crimes and only the most fastidiously politically correct reader would find either of these magnificently entertaining thrillers offensive. If you can bracket “realism,” police procedure, and CSI for a few hours, plunge into Rohmer’s pulse-thumping prose and fin-de-siècle atmosphere, filled with the opium dens and foggy Limehouse docks of a long lostLondon. You’ll be delighted, even if your guilty conscience cringes at the mention of “yellow devils” and the “fiendish Asiatic race.”

The idea of a “yellow peril,” a threat to the white race from a growing Asian geo-political power, seems to have arisen in the 1890s in German fears about Japanese expansion. But the term earned pulp currency in 1898 in the weird fiction writer M. P. Shiel’s serial The Empress of the Earth, later published in novel form as The Yellow Danger. Others less talented picked up the idea, but it wasn’t limited to writers of pulpy trash. Jack London’s The Unparalleled Invasion (1910) uses it, and it also forms the backdrop to Andrei Bely’s hallucinatory modernist novel Petersburg (1913), where it is called the “Mongol Peril” – Russians were afraid of the East, too - and it runs through the Polish avant-gardist Witkacy’s unclassifiable work Insatiability (1927), where it is presented as a Chinese takeover ofEurope. The central idea was thatAsia was breeding a new force, capable of overthrowing Western dominance, and that we should take steps to defeat it. Rohmer took this sensational theme and ran with it.

But fears of an Asian invader could not have secured Rohmer’s success alone. What carries both of these immensely enjoyable books is Rohmer’s ability to interweave his fantastic, bracingly unbelievable plots with the arcane knowledge he picked up over the years, an erudition that Fu Manchu of course puts to diabolical use. Rather than the crude bombs and vulgar bullets of other criminals, Fu Manchu employs Dacoits and Thugees (Indian bandits and assassins), drugs (mostly hashish and opium), pythons, spiders and other poisonous insects, poisonous mushrooms (occasionally an hallucinogenic one), germ warfare, and even a marmoset, in his fiendish designs.

Rohmer himself was self-taught and a keen student of the occult and esoteric; it is said that he belonged to the celebrated Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, of which Aleister Crowley and W.B Yeats were members, but this may be apocryphal. Whether he did or not, he did some research into magic – his one work of non-fiction, The Romance of Sorcery (1915), is a product of it – and although it is sometimes only hinted at, an air of the supernatural breathes throughout all his work. It is this mixture of the arcane, the outré, and the exotic, with an adrenaline fuelled narrative, that gives the Fu Manchu books their unmistakable appeal. And if in Fu Manchu Rohmer encapsulated western fears of an Asian threat, in the character of the Arab slave girl Kâramanéh, forced to do the evil Doctor’s bidding, he embodied –literally – all of its exotic allure. Dr. Petrie falls in love with Kâramanéh, with her “eyes like the velvet darkness of the East,” and his attentions are reciprocated. If we want to get semiotic about it, we could say that in Fu Manchu and Kâramanéh, Rohmer personalizes the West’s millennial fear of the mysterious East as well as its irresistible attraction, the seductive Other we at once pursue and repel, an addictive relationship going back at least to The Arabian Nights and Gérard de Nerval’s Journey to the Orient. I’m sure there’s an academic thesis about this somewhere, but it would be thin fare next to Rohmer’s rollicking tales.

Rohmer himself had an unusual life and he only came to fiction after unsuccessful attempts at earning an honest living as a civil servant, clerk, and reporter. Rohmer was born in Birminghamin England’s West Midlandsin 1883 to Irish immigrant parents. His father was an underpaid and overworked office clerk and his mother a highly-strung woman who slowly sank into alcoholism. Rohmer spent a great deal of his childhood alone and unattended; one possible product of his feral youth was a somnambulism which had him on occasion throttling his father and trying to jump out a window. For a time he wrote songs and comedy sketches for London music hall comedians, and in 1911 he ghost wrote the autobiography of Little Tich, one of the most famous. Although he never made it to China, Rohmer did travel in Egyptand the Middle East. One of his most effective novels, Brood of the Witch Queen (1918), has a series of murders carried out via the dark magic of the fabled Book of Thoth. Rohmer also developed other central characters and based other series on them. There was Gaston Max, a Parisian detective, who debuted in The Yellow Claw (1915); Morris Klaw, the Dream Detective, a Jewish East End curio-seller who solves crimes via the Kabbalah; and Sumuru, a buxom super-villainess – Russ Meyer would have approved - who also made it to the big screen in The Million Eyes of Sumuru (1967) an obtainable cult-classic, and the sequel That Girl From Rio (1969), as well as Sumuru (2003).

Although the Boxer Rebellion may have primed the public for Fu Manchu, Rohmer claimed that the Doctor had a real life prototype. While working for a Fleet Street tabloid in 1911, Rohmer was assigned to write an article about the Chinese underworld ofLondon’s Limehouse, today a desirable “historical” location, but back then a dockside warren of crime, decadence, and danger. He had heard stories about a mysterious “Mr. King,” who was purported to be the mastermind behind Limehouse’s evil economy of drugs, sex, and gambling. Access to Mr. King was understandably limited, and he never met him, but Rohmer did manage a sighting. When a “tall, dignified Chinese, wearing a fur-collared overcoat,” stepped out of the car, Rohmer knew that he had seen Fu Manchu, whose “face was the living embodiment of Satan.” He was never sure whether the man he saw was Mr. King or not, but by then that hardly mattered.

In the later books, Fu Manchu’s objectives change, and the emphasis on the threat to the white race recedes. By the end he is fighting Communism, and is, if not a friend, at least a tactical ally with the West. Popular taste in evil Asians had also changed. Earl Derr Biggers’ amiable Chinese detective Charlie Chan appeared in 1925, Mr. Moto, John Marquand’s Japanese secret agent, turned up in 1935, and Hugh Wiley’s Mr. Wong, the San Francisco sleuth, in 1938. These stories too have been accused of racism, but at least the moan of contention surrounds a good guy. Enjoy.

The Beast’s Last Days

I’ve contributed a long essay to a book about the last days of Aleister Crowley, and where he spent them. If Crowley puts you off, let me say that Netherwood: The Last Resort of Aleister Crowley is a fascinating literary and historical study about a remarkable boarding house in Hastings, England, that saw a curious collection of writers, philosophers, wits, and other eccentric characters pass through its doors. It is also beautifully put together, a unique item in every way, and should appeal to those with discerning tastes.

Swedenborg Goes to Washington

Here’s a review of Swedenborg, my book on him, and me in the Washington Post.

Swedenborg and the Huffington Post

Here’s a link to my guest blog at the Huffington Post, providing several reasons why you should know about Swedenborg.

From Blondie to Swedenborg, with Several Stops Along the Way

Here’s an interview with me about my book Swedenborg: An Introduction to His Life and Ideas, by the religion writer Mark Oppenheimer in the New York Times. I think the last time I was in the Times was in 1977, in a review of the Blondie album. Nice to be back.

What’s Left When There’s No Right

This review of Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary originally appeared in The LA Review of Books

Iain McGilchrist

The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World

Yale University Press, November 2010. 544 pp.

For millennia it’s been known that the human brain is divided into two hemispheres, the left and the right, yet exactly why has never been clear. What purpose this division served once seemed so obscure that the idea that one hemisphere was a “spare,” in case something went wrong with the other, was taken quite seriously. Yet the idea that the brain’s hemispheres, though linked, worked independently has a long history. As early as the third century B.C., Greek physicians speculated that the brain’s right hemisphere was geared toward “perception,” while the left was specialized in “understanding,” a rough and ready characterization that carries into our own time. In the 1970s and 1980s, the “split brain” became a hot topic in neuroscience, and soon popular wisdom produced a flood of books explaining how the left brain was a “scientist” and the right an “artist.”

Much insight into human psychology can be gleaned from these popular accounts, but “hard” science soon recognized that this simple dichotomy could not accommodate the wealth of data that ongoing research into hemispheric function produced. And as no “real” scientist wants to be associated with popular misconceptions — for fear of peer disapproval — the fact that ongoing research revealed no appreciable functionaldifferences between the hemispheres — they both seemed to “do” the same things, after all — made it justifiable for neuroscientists to put the split-brain question on the back burner, where it has pretty much stayed. Until now.

One popular myth about the divided brain that remained part of mainstream neuroscience was the perception of the left brain as “dominant” and the right as “minor,” a kind of helpful but not terribly important sidekick that tags along as the boss deals with the serious business. In his fascinating, groundbreaking, relentlessly researched, and eloquently written work, Iain McGilchrist, a consultant psychiatrist as well as professor of English — one wants to say a “scientist” as well as an “artist” — challenges this misconception. The difference between the hemispheres, McGilchrist argues, is not in what they do, but in how they do it. And it’s a difference that makes all the difference.

Although each hemisphere is involved in virtually everything the brain does, each has its own take on the world, or attitude toward it, we might say, that is radically opposed to that of the other half. For McGilchrist, the right hemisphere, far from minor, is fundamental — it is, as he calls it, “the Master” — and its task is to present reality as a unified whole. It gives us the big picture of a living, breathing “Other” — whatever it is that exists outside our minds — with which it is in a reciprocal relationship, bringing that Other into being (at least for our experience) while it is itself altered by the encounter. The left hemisphere, although not dominant as previously supposed, is geared toward manipulating that Other, on developing means of controlling it and fashioning it in its own likeness. We can say that the right side presents a world for us to live in, while the left gives us the means of surviving in it. Although both hemispheres are necessary to be fully alive and fully human (not merely fully “functioning”: a left brain notion), their different perspectives on the outside world often clash. It’s like looking through a microscope and at a panorama simultaneously. The right needs the left because its picture, while of the whole, is fuzzy and lacks precision. So it’s the job of the left brain, as “the Emissary,” to unpack the gestalt the right presents and then return it, increasing the quality and depth of that whole picture. The left needs the right because while it can focus on minute particulars, in doing so it loses touch with everything else and can easily find itself adrift. One gives context, the other details. One sees the forest, the other the trees.

It seems like a good combination, but what McGilchrist argues is that the hemispheres are actually in a kind of struggle or rivalry, a dynamic tension that, in its best moments (sadly rare), produces works of genius and a matchless zest for life, but in its worst (more common) leads to a dead, denatured, mechanistic world of bits and pieces, a collection of unconnected fragments with no hope of forming a whole. (The right, he tells us, is geared toward living things, while the left prefers the mechanical.) This rivalry is an expression of the fundamental asymmetry between the hemispheres.

Although McGilchrist’s research here into the latest developments in neuroimaging is breathtaking, the newcomer to neuroscience may find it daunting. That would be a shame. The Master and His Emissary, while demanding, is beautifully written and eminently quotable. For example: “the fundamental problem in explaining the experience of consciousness,” McGilchrist writes, “is that there is nothing else remotely like it to compare it with.” He apologizes for the length of the chapter dealing with the “hard” science necessary to dislodge the received opinion that the left hemisphere is the dominant partner, while the right is a tolerated hanger-on that adds a splash of color or some spice here and there. This formulation, McGilchrist argues, is a product of the very rivalry between the hemispheres that he takes pains to make clear.

McGilchrist asserts that throughout human history imbalances between the two hemispheres have driven our cultural and spiritual evolution. These imbalances have been evened out in a creative give-and-take he likens to Hegel’s dialectic, in which thesis and antithesis lead to a new synthesis that includes and transcends what went before. But what McGilchrist sees at work in the last few centuries is an increasing emphasis on the left hemisphere’s activities — at the expense of the right. Most mainstream neuroscience, he argues, is carried out under the aegis of scientific materialism: the belief that reality and everything in it can ultimately be “explained” in terms of little bits (atoms, molecules, genes, etc.) and their interactions. But materialism is itself a product of the left brain’s “take” on things (its tendency toward cutting up the whole into easily manipulated parts). It is not surprising, then, that materialist-minded neuroscientists would see the left as the boss and the right as second fiddle.

The hemispheres work, McGilchrist explains, by inhibiting each other in a kind of system of cerebral checks and balances. What has happened, at least since the Industrial Revolution (one of the major expressions of the left brain’s ability to master reality), is that the left brain has gained the upper hand in this inhibition and has been gradually silencing the right. In doing so, the left brain is in the process of re-creating the Other in its own image. More and more, McGilchrist argues, we find ourselves living in a world re-presented to us in terms the left brain demands. The danger is that, through a process of “positive feedback,” in which the world that the right brain “presences” is one that the left brain has already fashioned, we will find ourselves inhabiting a completely self-enclosed reality. Which is exactly what the left brain has in mind. McGilchrist provides disturbing evidence that such a world parallels that inhabited by schizophrenics.

¤

If nothing else, mainstream science’s refusal to accept that the whole can be anything more than the sum of its parts is one articulation of this development. The right brain, however, which knows better — the whole always comes before and is more than the parts, which are only segments of it, abstracted out by the left brain — cannot argue its case, for the simple reason that logical, sequential argument isn’t something it does. It can only show and provide the intuition that it is true. So we are left in the position of knowing that there is something more than the bits and pieces of reality the left brain gives us, but of not being able to say what it is — at least not in a way that the left brain will accept.

Poets, mystics, artists, even some philosophers (Ludwig Wittgenstein, for example, on whom McGilchrist draws frequently) can feel this, but they cannot provide the illusory certainty that the left brain requires: “illusory” because the precision such certainty requires is bought at the expense of knowledge of the whole. The situation is like thinking that you’re in love and having a scientist check your hormones to make sure. If he tells you that they’re not quite right, what are you going to believe: your fuzzy inarticulate feelings or his clinical report? Yet because the left brain demands certainty — remember, it focuses on minute particulars, nailing the piece down exactly by extracting it from the whole — it refuses to accept the vague sense of a reality larger than what it has under scrutiny as anything other than an illusion.

This may seem an interesting insight into how our brains operate, but we might ask what it really means for us. In a sense, all of McGilchrist’s meticulous marshalling of evidence is in preparation for this question, and while he is concerned about the left brain’s unwarranted eminence, he in no way suggests that we should jettison it and its work in favour of a cosy pseudo-mysticism. One of his central insights is that the kind of world we perceive depends on the kind of attention we direct toward it, a truth that phenomenologists like Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger — both invoked by McGilchrist — established long ago. In the homely maxim, to a man with a hammer everything looks like a nail. To the right brain, the world is — and, if we’re lucky, its “isness” produces in us a sense of wonder, something along the lines of a Zen satori or a sudden delight in the sheer interestingness of things. (As Heidegger and a handful of other thinkers said, that there should be anything rather than nothing is the inescapable mystery at the heart of things, a mystery that more analytical thinkers dismiss as nonsense.)

To the left brain, on the other hand, the world is something to be controlled, and understandably so, as in order to feel its “isness” we have to survive. McGilchrist argues that in a left-brain dominant world, the emphasis would be on increasing control, and the means of achieving this is by taking the right brain’s presencing of a whole and breaking it up into bits and pieces that can be easily reconstituted as a re-presentation, a symbolic virtual world, shot through with the left brain’s demand for clarity, precision, and certainty. Furthermore, McGilchrist contends that this is the kind of world we live in now, at least in the postmodern West. I find it hard to argue with his conclusion. What, for example, dotechnologies like HD and 3D do other than re-create a “reality” we prefer to absorb electronically?

McGilchrist contends that in pre-Socratic Greece, during the Renaissance, and throughout the Romantic movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the two hemispheres reached a brilliant accord, each augmenting the other’s contribution. Through their creative opposition (as William Blake said, “Opposition is True Friendship”) they produced a high culture that respected the limits of certainty and honored the implicit, the tacit, and the ambiguous (Keats’s “negative capability”). But since the Romantics, the left brain has increasingly gained more ground; our use of “romantic” as a pejorative term is itself a sign of this. With the rise of modernism and then postmodernism, the notion that there is anything outside our representations has become increasingly jejune, and what nature remains accessible to us is highly managed and resourced. McGilchrist fears that in the rivalry between its two halves, the left brain seems to have gained the upper hand and is steadily creating a hall of mirrors, which will soon reflect nothing but itself, if it doesn’t do so already.

The diagnosis is grim, but McGilchrist does leave some room for hope. After all, the idea that life is full of surprises is a right brain insight, and as the German poet Hölderlin understood, where there is danger, salvation lies also. In some Eastern cultures, especially Japan, where the right brain view of things still carries weight, McGilchrist sees some possibility of correcting our imbalance. But even if you don’t accept McGilchrist’s thesis, the book is a fascinating treasure trove of insights into language, music, society, love, and other fundamental human concerns. One of his most important suggestions is that the view of human life as ruthlessly driven by “selfish genes” and other “competitor” metaphors may be only a ploy of left brain propaganda, and through a right brain appreciation of the big picture, we may escape the remorseless push and shove of “necessity.” I leave it to the reader to discover just how important this insight is. Perhaps if enough do, we may not have to settle for what’s left when there’s no right.

¤

Gary Lachman is the author of more than a dozen books on the links between consciousness, culture, and the western counter-tradition, including Jung the Mystic, and A Secret History of Consciousness. He is a contributor to the Independent on Sunday, Fortean Times, and other journals in the US and UK, and lectures frequently on his work. A founding member of the pop group Blondie, as Gary Valentine he is the author of the memoir New York Rocker: My Life in the Blank Generation.http://bit.ly/vYVmpN

Secret Societies

This is the text of an “audio essay” I wrote for the exhibition Geheim Gesellschaften or “Secret Societies,” held at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, Germany, this summer. The exhibition is moving to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Bordeaux in November, and on the 23rd of November I will be speaking there on the influence of secret societies on the modern world.

Secret societies have existed almost as long as society has itself. The initiates of ancient Egypt; the priest-kings of China; the acolytes of the Greek Mysteries;the shamans of humanity’s early dawn; the holy masters in their inner sanctums in the hidden cities of the world – all are alive today, and work their strange practices and issue their commands, unknown, unsuspected, and undetected by us.

The Secret Chiefs, the Hidden Masters, the Inner Circle, the Illuminati, the King of the World: we know them all today, perhaps in different forms and perhaps by different names. But we know them. They are the ones in control. They are ones behind the closed doors and within the locked rooms. They are the ones with the secret knowledge, who speak a secret language. They know the magic symbols that unlock the gates that lead to worlds beyond our own. They have passed through the trials and ordeals of initiation. They have found the Holy Grail, the Philosopher’s Stone, the Emerald Tablet, the dreaded Necronomicon and the lost continent of Atlantis.

Many have belonged to this school. Some say Buddha, Christ, and Plato were its students. There were others too, names so great that to mention them in the context of secret schools would shock the uninitiated. All received the secret knowledge and kept it from profane hands. They have spoken with the angels and listened to the music of the spheres. They have travelled to the interior of the earth and brought back the precious metals of the mind. They have confronted the awful Dweller on the Threshold and they know the song the sirens sang. They have taken the Journey to the East and followed the bark of Ra as it sinks into the west. They have set their controls for the heart of the sun. They built the pyramids and the Sphinx, Stonehenge and Notre Dame, the lost library ofAlexandriaand the labyrinth atChartres. They are the elite. They are the elect. They are the few who know, who dare, who will – and who keep silent.

They might be anyone. According to the Russian philosopher P.D. Ouspensky – himself a member of an esoteric society and a lifelong seeker of theInner Circleof Humanity – much secret knowledge was learnt from an Oriental who sold parrots atBordeaux. Ouspensky’s own search for the miraculous and ‘unknown teachings’ led to an unprepossessing café in aMoscowbackstreet, where, after all his travels in the mystic East, he finally found The Man Who Knows.

He might be sitting next to you, or perhaps you passed him on the street. “Knock,” the Gospels tell us, “and it shall be opened unto you; ask and you shall receive.” But you must know where to knock and you must know who to ask. And you must first understand that the entire universe is a secret message, an enormous letter in a bottle made of space and time, washed ashore by the tides of eternity. You must look. You must question. You must take nothing for granted. You must be willing at a moment’s notice to give up everything – riches, position, power, your life – in order to have a single chance of passing from our everyday world, which we think we know so well, to that other world, that world of mystery, magic, miracle, and the unknown. That hidden, dangerous, seductive world of secret societies.

When you take that step, many things become possible. From then on nothing is true, and everything is permitted. From then on you may do what you will for, as the poet William Blake tells us, this world, the world you have left behind, is a fiction, made up of countless contradictions. This ‘real’ world, this world of newspapers, mobile phones, and internets, is, for those who have taken that fatal step, false. It is a trap, a prison house of the soul, where mind and body are constrained by the chains of ignorance and fear, the Archons of convention who keep us unaware of the knowledge, the gnosis, that will set us free. In the world of secret societies knowledge is power, and power is the power to know. It is the knowledge that you have the power to change the world by changing your knowledge of it. The secret writing, the hidden doctrine, the magical correspondences between above and below, lie beneath the thin surface text of everyday life. Here and there cracks appear in the mundane shell and we can briefly catch a glimpse of the real writing. We see connections, patterns, relations between the most disparate things.

As Edgar Allan Poe tells us in “The Purloined Letter,” that which is most hidden is open to view, provided you know how to look for it. Poe’s ‘spiritual detective’ is good at discovering secrets in plain sight. He wears dark glasses at night and keeps his shutters closed and his lamp burning by day. This reversal of the everyday world opens his imagination and enables him to see what everyone else is blind to, but which is in plain view. Like his creator himself, Poe’s detective is a member of the secret society of poets – for what is a poet but a discoverer of secrets that others do not know exist?

Now, with your eyes wide shut look around you and listen to the voices whispering loud and clear. Do not be afraid. Remember, each symbol is a doorway into your Self. The magic theatre waits; it is open for madmen only. As above, so below, and as within, so without. “When we dream that we are dreaming,” the seeker of the blue flower tells us, “we are close to awakening.” You approach the portal and must decide. Are you willing to take the risk? Are you ready to have your world turned upside down? Are you ready to join a society whose members know each other at a glance, who pay no dues, take no minutes? Whose meetings last the ages and take place among the Himalayas, onEgypt’s burning sands, and in the sunken cities of lost worlds? Do you want to know a secret?

Initiation

The candidate for initiation is a man or woman who is ready to change, to be transformed, to become someone different. If it is not a mere parroting of ritual, an initiation ceremony should have a serious effect upon the candidate. He or she should be a different person afterwards. Rebirth and regeneration are the signs that the initiation has been successful. This is usually achieved through some ordeal. Death and violence are never far from an initiation. As the esoteric historian Manly P. Hall tells us, “many of the great minds of antiquity were initiated into secret fraternities by strange and mysterious rites, some of which were extremely cruel.”

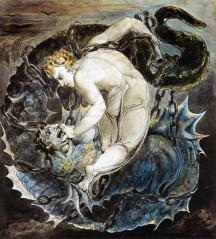

In the initiation rites of Freemasonry, the candidate re-enacts the murder of the ancient master builder Hiram Abiff, killed by three ‘ruffians’ because he would not reveal the secret Mason’s word. Daggers, a noose, and severe interrogation mark the candidate’s rite of passage. The initiate himself must swear eternal silence about these profound secrets, on pain of torture and death, should he reveal them to the profane, a commitment shared by all the great esoteric societies – hence the fact that we know so little about them. These Masonic rites themselves, or so it is believed, are based on the initiation ceremonies of the ancient Egyptians, a people whose whole society was ordered according to the ancient wisdom guarded by the high priests. In secret chambers built deep into the pyramids and below the temples of their gods, the ancient Egyptians performed rites, dramatic re-enactments of the struggle of the soul in its passage through the underworld after death. Based on the mysterious Book of the Dead, through ceremony, trance, trial, and terror, the Egyptian initiate experienced the journey of the soul through the fearful world of the Duat, that strange region inhabited by demons, gods, and the darker spirits of his own nature, while still alive. Passing through successfully he joined his fellow initiates as a soul freed from the terror of death, and took his place among them amidst the eternal stars.

As the journey to the stars took place via the underworld, many initiation rites were performed in sunken chambers, in caves and grottoes, which symbolized the fallen nature of the Earth. Below the temple of the god Serapis in ancient Alexandria– destroyed in 391 AD by the Roman emperor Theodosius – strange mechanical devices constructed by the ancient priests were found in subterranean crypts and caverns, where the initiatory trials were undergone. In the worship of the lost Persian saviour-hero Mithras, initiation rites were performed in underground temples fashioned to look like caves, which the initiate entered by descending seven steps – representing the ancient planets – and upon whose walls were painted mystic symbols. Here the candidate underwent grievous trials, where he was pursued by the wild beasts and demons of his lower nature. Part of the Mithraic rites involved the tauroctony, or sacrifice of a bull, in which Mithras, the intercessor between man and the gods, stabs the animal with a sword, while turning his face toward the sun.

The theme of a sunken, subterranean, and secret chamber is found in many secret societies. In the myth of Christian Rosenkreutz, founder of the 17th century esoteric society the Rosicrucians, his uncorrupted body is discovered more than a century after his death, hidden in a seven sided underground vault, lit by a miniature sun, and surrounded by occult symbols. This image of a sun hidden in the earth – light sunken into darkness – was carried by the underground streams of esoteric thought into western literature, and appears, for example, in that remarkable compendium of secret knowledge, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, by the eccentric 18th century Polish Count Jan Potocki. Potocki himself was involved in several secret societies; among them the sinister Illuminati. In his highly esoteric work, structured like the Arabian Nights (itself a treasure chest of secret lore), after confronting the sheik of a secret Islamic sect, his hero finds himself descending into a subterranean cave, illuminated by innumerable lamps, where he extracts from the dark earth the precious Rosicrucian gold of enlightenment.

Some secret schools, such as the ancient Magi, devotees, like the followers of Mithras, of a form of Zoroastrianism, performed their initiations in the open air, on mountain tops, without temples, altars, or images, and with the entire cosmos as a backdrop. Others, like the Druids, sought out hidden fields and woods, a preference shown by the renegade French surrealist Georges Bataille. Fascinated by the idea of human sacrifice ( a practice associated with the Druids) in 1936 Bataille formed a secret society (as well as a journal) named Acéphale – ‘headless’ – whose symbol was a decapitated Vitruvian Man, a mutilated version of Da Vinci’s famous drawing, holding a dagger, with stars for nipples, exposed entrails, and a skull in place of the genitals. Their meetings were held in forests and woods and Bataille, whose headless man depicts Dionysian frenzy and excess, planned for one member to become a human sacrifice. The ritual murder would link the others in a pact of blood, but plans for Bataille’s gory initiatory crime were aborted shortly before the outbreak of World War II.

Following his passage into the new life, the initiate is introduced to the structure of the society he has joined, to the secret knowledge it protects, and to the secret language its members use to speak among themselves. He takes a solemn oath to preserve these sacred revelations, which, as mentioned, he must protect with his life. Family, friends, possessions, position, religion – all now take a secondary role. His new loyalty is to his new brothers and sisters, and even more so to his leaders, his superiors in knowledge and power, whose identity he often does not know.

Hidden Masters

The theme of Hidden Masters, Secret Chiefs, Unknown Superiors, and Mysterious Mahatmas is one shared by many secret societies, ancient and modern. In the west it is perhaps best expressed in the curious history of the Rosicrucians. In 1614 inKassel,Germany, pamphlets appeared announcing the existence of a mysterious society of adepts, known as the Rosicrucians, whose mission was the ‘universal reformation’ ofEurope. This unknown group of philosophers called on their readers to join them in their work of creating a newEurope, freed from religious, social, and political repression. Many indeed were attracted to this message and sought out the mysterious brotherhood, among them the philosopher René Descartes. Yet try as Descartes and others may to contact the secret brothers, no one could ever find them. Their whereabouts, it seemed, were unknown, and because of this the Rosicrucians soon attracted a new title, “the Invisibles.”

To some, the Rosicrucians’ ‘invisibility’ meant simply that they did not exist, and that the whole Rosicrucian craze was merely a hoax. Yet others rejected this idea, saying that, like their founder, Christian Rosenkreutz, they had gone into hiding, and only revealed themselves to the most worthy. Following the outbreak of the Thirty Years War, some said they had left Europe altogether and relocated toTibet, a place even then associated with Hidden Masters.

Freemasonry, too, has its own Hidden Masters. In the esoteric rite of Strict Observance, founded in the 18th century by the mysterious German Baron Karl Gottlieb von Hund, initiates must take a vow of absolute loyalty to masked figures known only as the ‘Unknown Superiors’, whose every command must be carried out with blind obedience. In the heady atmosphere preceding the French Revolution, Hund’s secret Masonic rites proved very popular, and the idea of secret leaders controlling events behind the scenes laid the groundwork for the conspiracy theories so widespread today. Stranger still was the belief that some Unknown Superiors were not simply men of position and power, but beings from another world. In the mystical Masonry of the Benedictine Antoine-Joseph Pernety, which combined Masonic ritual with mesmerism and the visions of the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, orders were issued, not from a fellow Mason, but by some strange unearthly entity Pernety called “the Thing.” A similar paranormal chain of command was at work in the mesmeric Masonry of Jean-Baptiste Willermoz, who received angelic orders from an “Unknown Agent” via the trance states of a group of women called the crisiacs.

By the late 19th century, a new variety of Hidden Masters appeared through the medium of the remarkable Russian esoteric teacher Madame Blavatsky, responsible for founding one of the most influential esoteric schools of modern times, Theosophy. Blavatsky claimed to be the agent of a secret group of highly evolved adepts, known variously as the Mahatmas, Masters, or Great White Brotherhood, whose provenance was India and whose base of operation was Tibet. Their real identity was unknown but messages from the Brothers miraculously appeared from nowhere, and were signed by secret names such as “Morya” and “Koot Hoomi.” Hints of the Theosophical Masters were soon linked to other legends of the East. One such was the strange myth of the King of the World, a powerful and sinister figure who resides in the subterranean city of Agartha, which lies unknown somewhere beneath the Gobi Desert. There he sits and “searches out the destiny of all peoples on the earth,” his sunken city linked to all nations through a vast network of tunnels. According to the 19th century occultist Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, founder of the secret political movement Synarchy, who was tutored in the ways of Agartha by the mysterious Haji Sharif, the King of the World is also known as the “Sovereign Pontiff.” His secret agents are at work in all corners of the globe, awaiting the signal to take the destinies of nations in hand, and prepare them for the King’s shattering appearance.

Less monumental but no less hidden are the Secret Chiefs whose edicts guided the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, perhaps the most well known secret occult society of modern times, which included among its members the poet W.B. Yeats and the infamous magician Aleister Crowley. Impatient with the speed of the Golden Dawn’s initiations, Crowleysought out his own Secret Chief, and in a hotel room in Cairoin 1904, he met him. Aiwass, a disembodied intelligence from another dimension, dictated to Crowleythe text of his most influential work, the notorious Book of the Law, the scripture for Crowley’s religion of Thelema. It’s message was “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.” Crowley proceeded to do what he wilt with great enthusiasm, among other ways by starting his own secret society, the Argentinum Astrum (‘Order of the Silver Star’), dedicated to Crowley’s peculiar blend of hedonism and magical philosophy. Many joined and today Crowley, once known as “the wickedest man in the world,” is an iconic figure within youth culture, his face and ideas informing a wide range of pursuits, from rock music – the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and many other groups were devotees - to drugs and sex.

In more recent times the notion of Hidden Masters or Secret Chiefs has entered more political realms, with Unknown Superiors appearing in the form of influential and powerful men, like the Bilderberg group, making secret decisions behind closed doors that affect – as did those of the King of the World – the destiny of nations. Conspiracy theories have their place in the world of secret societies, but they are, in essence, more of an offshoot than the main branch. Political conspiracies may revolve around important knowledge, but it is knowledge on only one level, that of the everyday world. The knowledge revealed to the initiates of the true secret societies is something very different. It is the secret knowledge relating to man and the cosmos.

Secret Knowledge

The idea of a hidden, unknown, esoteric knowledge runs like a golden thread throughout the history of secret societies. It is the secret of the Holy Grail, the true meaning of the Philosopher’s Stone, the mysterious treasure of the Knights Templar, and the haunting face of the unveiled Isis. It is the genii of Aladdin’s lamp and the magic of Jason’s Golden Fleece. It is the guarded secret of the Eleusinian Mysteries, and the answer to the riddle of the Sphinx. It is known by many names and it is hidden in many places, but its meaning is one and all who seek it, honestly and with patience, find the same treasure and reap the same reward. “Behind the veil of all hieratic and mystical allegories, behind the strange ordeals of initiation, behind the seal of all sacred writings, in the ruins of old temples, and in the ceremonies practiced by all secret societies,” so the 19th century French Cabbalist Eliphas Levi reveals, “there is found a doctrine which is everywhere the same and everywhere carefully concealed.” This doctrine, the Ancient Wisdom, has been handed down through the ages from sage to sage, initiate to initiate, its profound revelations carefully guarded by the keepers of the secret Book. At its core is the perennial philosophy, the prisca theologia, the divine wisdom revealed to man by the gods at the dawn of time. Through knowledge of the secret doctrine, man becomes aware of his true place in the cosmos, escapes the fear of death, and knows that his real essence is of the gods.

Many have sought the secret knowledge, and journeyed to distant lands to find it. With other members of the Seekers of Truth, the 20th century Greek-Armenian esoteric teacher G. I. Gurdjieff travelled toCentral Asia, in search of the hidden monastery of the fabled Sarmoung Brotherhood. There he encountered the Masters of Wisdom, agents of theInner Circle of Humanity, who accepted him as a student, and passed their knowledge on to him. In a secret monastery in forbiddenTibet, Madame Blavatsky lived for seven years, tutored by her mysterious Mahatmas in the teachings of the secret doctrine, absorbing the ancient wisdom that is at the core of all religions and esoteric thought. Christian Rosenkreutz himself had journeyed through the near East, the holy land and North Africa, arriving at the secret city ofDamcar, where he studied ancient and forbidden writings that taught the mystical truths about man and the cosmos. On his own journey to the East in search of secret schools, P. D. Ouspensky met others who were on the same journey, and it felt to him that a “secret society” grew out of these contacts, having no name, no structure, no laws, but was formed solely by their intense hunger for knowledge and passionate quest for truth.

Others have sought the secret knowledge in other ways, in ancient myths, in fairy tales, in the ruins of lost cultures and the fragments of lost worlds. In the labyrinth of Chartres Cathedral and the gargoyles of Notre-Dame de Paris, the mysterious 20th century alchemist Fulcanelli discovered a secret text, a philosophy in stone that transmits, to those who can see it, the fundamental truths of the universe. The medieval builders, Fulcanelli believed, were agents of an esoteric school, and carved into these Gothic masterworks, secret knowledge of the cosmos. Ages before, on the sands of ancientEgypt, the high priests of Isis and Osiris built enormous temples whose geometry embodied the wisdom of the gods, a theosophy in obelisks and strange colossi. To those who know how to read them, the Sphinx, the hieroglyphs, the pyramids are all chapters of a hidden book, a sacred scripture, a monumental text, revealing the mysteries of life and death. Other “syllables of granite” spoke of the mysteries too. According to Victor Hugo, who recognized in Notre Dame a great symphony of knowledge, “the immense pile of Carnac” – in Brittany – “is a complete sentence” expressing the lost wisdom of a people long gone.

To some, the secret knowledge comes in a flash, a sudden overwhelming revelation, like a lightning bolt of insight from the divine. So did the Universal Mind speak to the ancient sage Hermes Trismegistus, when it revealed to him the truth that man is a microcosm, a “little universe,” whose mind itself contains the galaxies and planets. So too did this cosmic consciousness come to others. Staring at the sunlight reflected from a pewter dish, the 17th century cobbler Jacob Boehme was suddenly privy to the “signatures of things”: their inmost essence was revealed to him and he gaze upon their true being. On 14 December 1914 the Lithuanian poet and diplomat O.V. de Lubicz Milosz had a mystical experience in which he rocketed through space carried along by a flying mountain, toward “nebulous regions silent and streaked by immense flashes of lightning.” A gigantic red egg hurtled toward him and was then transformed into a glowing “spiritual sun” which looked deeply into his eyes and revealed to him secrets of space and time. Milosz captured this vision in strange poetry full of mystical arcana, whose insights mirrored those of Einstein and revealed to him the mind of God. Other poets sought the secret knowledge in other ways. Obsessed with piercing the mute surface of things, the young Arthur Rimbaud, a great reader of mysticism and the occult, dedicated himself to becoming a visionary, a voyant. To do so Rimbaud threw himself into a “long, immense, and systematic derangement of the senses,” an initiation into altered states of consciousness that he hoped would open for him the hidden doors of perception.

The secret knowledge, however, is not for everyone. Like Poe’s “purloined letter,” in many ways it lies open to view, there for the taking if only one can see. But although our eyes are open we may still be blind, ignorant of the messages written in the things around us. Like travellers in a foreign land, we need to learn a strange tongue, a new language that will provide the key to unlock the hidden mysteries. This language is not given in dictionaries and guide books, but in the mysterious emblems, images, shapes and forms that make up the secret world of symbols.

Symbols

“Without the help of symbols,” so Madame Blavatsky tells us, “no ancient scripture can ever be correctly understood.” “The great archaic system known from prehistoric ages as the sacred Wisdom Science,” she tells us, “had it’s universal language, the language of the Hierophants.” This master esoteric teacher is not alone in recognizing the absolute necessity of grasping the ancient language of symbols. In The Hidden Symbolism of Alchemy and the Occult Arts, the psychologist Herbert Silberer, a colleague of Freud and Jung, tells us that, “Symbolism is the most universal language that can be conceived.” “Symbols,” Silberer tells us, “strike the same chords in all men, and the individual, with every spiritual advance he makes, will always find something new in the symbols already familiar to him.” Speaking of the mysterious universal symbol of the nine-pointed enneagram, which is at the centre of his teaching, Gurdjieff told Ouspensky that it included all knowledge, and that by understanding it, books and libraries become unnecessary. “A man can be quite alone in the desert,” Gurdjieff said, “and he can trace the enneagram in the sand and he can read the eternal laws of the universe. And every time he can learn something new, something he did not know before.” And what is true of the enneagram is also true of all symbols: the pentagram, the hexagram, the yin and yang, the cross, the eye in the triangle. Their meaning is not exhausted by repeated meditation, but increased, just as great works of music, art, and literature reveal new depths and new dimensions each time we come to them with new eyes and ears.

Symbols have their great power because, unlike everyday words or pictures, they reach into the soul and transform it – again, just as great art does. In this way symbols have an initiatory character, and a true grasp of them has a palpable effect upon our consciousness. Unless we are changed by them, we do not know them, no matter how learned our understanding of them may be. They speak not only to the mind, the rational, questioning intellect, but to our whole being, and to parts of ourselves of which we are too often ignorant. According to the anonymous author of Meditations on the Tarot, one of the great works of 20th century esotericism, symbols “awaken new notions, ideas, sentiments and aspirations” and “require an activity more profound than that of study and intellectual explanation.” Symbols conceal and reveal simultaneously that which it is necessary to know in order to fertilize our inner life. To those uninitiated into their secrets, they are merely curious pictures and strange images which, once explained, trouble us no more. But to those who know, they are the seeds of new life. They are a ‘ferment’ or ‘enzyme’ that stimulates our spiritual and psychic growth. They must, then, be approached with reverence and in secret. We must withdraw into ourselves in order to be immersed in them, to meditate on them and to allow them to reach inside our deepest being. Hence the need for solitude, silence, patience, and respect when approaching the language of symbols.

One aspect of the signs, symbols, and languages of secret societies is as a kind of camouflage, a disguise worn to prevent the uninitiated from gaining access to the hidden knowledge. The ancient Masons recognized each other by certain handshakes and words, and through these prevented outsiders from infiltrating their ranks. The medieval alchemists spoke in a strange, surreal, dream-like language of green dragons and red lions, of sulphur, mercury, and salt, of alembics and retorts, of solar kings and lunar queens who come together in weird androgynous unions to produce the Philosopher’s Stone. Reading their illuminated texts, one enters a terrain of shifting, changing contours, a metamorphosis of identities that is baffling, unless one possesses the key to decipher it. The Gothic architects too developed a peculiar argot, a “green language” (langue verte), a kind of “word play” that, again according to Fulcanelli, “teaches the mystery of things and unveils the most hidden truths” while at the same time remaining “the language of a minority living outside accepted laws, customs, and etiquette.” Through puns, jokes, double entendres and homonyms, this “phonetic cabala” at once communicated secret knowledge to those who knew, and obscured it from those outside the fold.

Passwords and secret signals are, it is true, an important part of secret societies. But they are merely an esoteric ‘firewall’, preventing human ‘viruses’ and ‘malware’ from entering the inner sanctum. Although it is necessary to keep the secrets secret – and hence obscured from profane view – the true essence of symbols is to communicate, and their hermetic, multiple character has always attracted poets. The great Portuguese modernist Fernando Pessoa, a confirmed occultist and passionate student of secret societies, wrote that “I believe in the existence of worlds higher than our own, and in the existence of beings that inhabit these worlds, and we can, according to the degree of our spiritual attunement, communicate with ever higher beings.” Pessoa trained himself to remain awake at the point of sleep, and in that twilight realm between two states of consciousness, he closed his eyes and saw “a swift succession of small and sharply defined pictures.” He saw, Pessoa tells us, “strange shapes, designs, symbolic signs, and numbers,” a parade of images similar to the occult signs and symbols, the Masonic and Cabbalistic insignia he perceived during his experiments with trance states. Like Rimbaud, Pessoa knew that initiation into the hidden knowledge may be achieved not only through the rites and ceremonies of a secret society, but through the passage from one form of consciousness to another. By opening the doors of perception and entering an altered state of consciousness, Pessoa, and others like him, reached the source of all mystic, esoteric, and magical symbols: the human mind itself.

Altered States

Human beings have desired to change their consciousness almost from the beginning of human consciousness itself, and if the findings of some researchers are correct, the taste for altered states of consciousness is shared by some animals too. Reindeer, birds, elephants, goats, and even ants have been observed to feel a desire to experience altered states. It seems that “the universal human need for liberation from the restrictions of mundane existence,” as the anthropologist Richard Rudgley puts it, is not limited to humans after all, and may itself be a fundamental drive of evolution.

The earliest forms of art may be linked to altered states. In some prehistoric sites, the strange spirals, swirling and curving parallel lines, and other highly complex geometric forms covering the cave walls, suggest the abstract imagery often associated with psychoactive experience. They also suggest the “strange shapes, designs and symbolic signs” Fernando Pessoa saw on the point of sleep, and which he believed were messages from “higher beings.” In Neolithic sites, such as the tomb of Gavrinis inBrittany, finely decorated braziers have been discovered, which some researchers have suggested were used in shamanic rituals in which opium was burned and inhaled in order to produce altered states. There is evidence also for cannabis use as a religious intoxicant in prehistoricEurope. Hemp seeds have been discovered in Neolithic sites inGermany,Switzerland,Austria, andRomania, and braziers similar to those discovered at Gavrinis containing burnt hemp seeds have been found in these locations. This suggests that they too were used in religious rituals, in which cannabis was burned to induce a change in consciousness. InChina, Central Asia, and theNear East, similar discoveries suggest that the use of cannabis and other psychoactive substances in religious rituals was widespread in the ancient world.

One of the oldest Hindu religious books, the Artharva Veda, speaks of drugs, their preparation and use, and many scholars have speculated on the identity of the mysterious Soma, an unknown plant whose psychoactive properties play a central role in the ancient religious texts of India and Iran. In the Iranian Avesta it is said that “all other intoxications are accompanied by the Violence of the Bloody Club, but the intoxication of Haoma is accompanied by bliss-bringing Rightness.” Some candidates for Soma include cannabis, alcohol, Syrian rue, opium, and Ephedra, possibly the earliest known psychoactive plant in human history. During excavations in the 1950s, remains of six Ephedra plants were found in a 50,000 year old Neanderthal grave in the Shanidar cave inIraq, suggesting that even our pre-homo sapiens ancestors were interested in altering their state of consciousness.

Another candidate for the mysterious Soma is the fly-agaric mushroom, known to be used by Siberian shamans in their mystical excursions into the spirit world. In the late 1960s, the American R. Gordon Wasson suggested that this sacred mushroom might be the answer to riddle of Soma. But the identity of the mysterious ancient drug remains unknown.

In the 1950s, Wasson had already made psilocybin or ‘magic mushrooms’ famous through his studies of their religious and initiatory use inMexico. There, Wasson learned much about the sacred mushroom from the healer María Sabina, who spoke of the secret knowledge she received through its use. It produced visions of “ancient buried cities, whose existence is unknown.” She “knew and saw God” and could see “inside the stars, the earth, the entire universe.” The mushroom took her beyond space and time, beyond life and death, and revealed to her a great Book that in an instant taught “millions of things.”

It was Wasson’s own experiences with sacred mushrooms that led him, and his colleagues Carl Ruck and Albert Hoffmann – the discoverer of LSD – to believe that some sort of psychoactive plant was the secret ingredient of the mysterious kykeon, the drink given to initiates of ancient Eleusinian Mysteries. Whatever it was, the kykeon produced a shattering revelatory experience, which all who shared swore never to reveal. Wasson, Ruck, and Hoffmann suggested that the parasitic fungus ergot, whose psychoactive alkaloids are similar to lysergic acid, was responsible for the mystical experience countless initiates underwent during the two millennia in which the Mysteries flourished.

As in the case of Soma, other drugs have also been proposed as the secret behind the Mysteries. Modern shamans, such as Terence McKenna, have argued that the sacred mushroom itself was responsible, and more recently the powerful South American Indian entheogen (‘within-god-making’) ayahuasca has become a popular candidate. Yet, as the truth of the Eleusinian Mysteries remained a secret for 2,000 years, and the Mysteries themselves have been gone for nearly as long - they were finally wiped out in 396 by Alaric, king of the Goths - we may never know their secret.

Yet the appeal of a sacred drug ceremony remains strong in the mythology of secret societies, and in the 1960s a new version of the ancient mysteries appeared in the form of the ‘psychedelic experience’. Its High Priest was the renegade Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary. Taking the esoteric Tibetan Buddhist guide to the afterlife, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, as a blueprint, Leary sought to ‘turn on’ a generation, dismissive of all authority and unhappy with the American Dream, to the mystery of LSD. Hippies, flower power, free love, and ‘dropping out’ were the products of the new, mind-blowing mysteries that rocked a nation already reeling from civil unrest and the Viet Nam War. By the end of the ‘mystic sixties’ what remained wasn’t the love and peace that many believed were on their way, but the dark suspicions of a ‘bad trip’. By the 1970s we had entered the Age of Paranoia.

Conspiracy Consciousness

For all their promise of hidden knowledge and profound initiations, the two most famous secret societies in history were adamantly political and sought not deep revelations about man and the cosmos, but ruthless power and control. Their names have come down to us and are synonymous with political terror and paranoia. Legend has it that in 1092 two men stood on the ramparts of the medieval castle of Alamut – “the Eagle’s Nest” – in the Persian mountains. One was a representative of the emperor; the other, a strange veiled figure who claimed to be the incarnation of Allah on earth. This mysterious character was Hassan-i-Sabbah, “the Old Man of the Mountains,” leader of the dreaded Hashishins, a secret society of political terrorists whose very name sparked fear throughout the medieval Muslim and Christian world. The emperor’s representative had come to ask Hassan to surrender, but Hassan had other plans. Pointing to a guard standing watch on a turret-top, Hassan told his guest to observe. At a signal from his master, the white-robed devotee saluted Hassan and without hesitation plunged two thousand feet into the rushing waters below. Such was the unthinking devotion with which the Assassins, as they came to be known, worshipped their holy leader. Faced with such fanaticism, the emperor’s representative retreated.

Many legends surround the Assassins, particularly on how they acquired their name. According to the 13th century traveller Marco Polo, Hassan would pick out likely candidates for his secret society and, after secretly drugging them with hashish – hence the name Hashishins - would take them to his luxurious pleasure gardens, kept in a secluded valley. Here streams of milk, honey, and wine skirted palaces ornamented with gold and precious jewels. Fragrant scents filled the air, and beautiful maidens displayed their charms. Hassan’s candidates remained here for some days until, once again drugged, they were returned to court. Hassan then explained that he had sent them toParadise, to which they would return if they served him faithfully. The devotee who cast himself from the top of the castle was proof of the persuasiveness of Hassan’s deception, and by this means the Old Man of the Mountain secured a large and efficient secret society of political assassins that, later ruled by his descendants, led a reign of terror for nearly two centuries.

Although the truth of these legends is questioned, what comes down to us is the seductive idea of being “beyond good and evil.” Hassan convinced his followers that he was above the law, and with them he shared the exhilarating revelation that “Nothing is true; everything is permitted.” This, with Aleister’sCrowley’ “Do what thou wilt,” has become a catch phrase of occult libertinism. Another political secret society has also become a part of esoteric legend. On 1 May 1776, Adam Weishaupt, a professor of canonical law atIngoldstat,Germany, founded the Bavarian Illuminati, a renegade Masonic group that sought to overthrow the repressive control of the Jesuits. Weishaupt infiltrated the Masons and drew candidates for his society by promising even deeper, secret knowledge and more elite initiations. Yet while he spread word of profound mystical knowledge, Weishaupt’s Illuminati was in truth a strictly rationalist group, adverse to all mysticism and religion, and driven by the Enlightenment ideals of science, atheism, and egalitarianism. His idea was to create a vast organisation and then reveal to an elite corps his secret aim: to rid the world of kings, queens, princes, and nations and establish a rational secular state. Weishaupt’s plan was at first successful, and among his Illuminists he numbered Goethe, Schiller, and Mozart, as well as the eccentric Count Potocki and the notorious Sicilian magician, Cagliostro. Yet his scheme soon backfired. Initiates who demanded even deeper revelations had to be informed of his deception and brothers who were scandalized by his plans spoke openly against them. Eventually the authorities learned of his designs and in 1784, membership in any secret society at all was outlawed throughoutBavaria.

Weishaupt faded into obscurity, but following the French Revolution, his secret society was resurrected in the imagination of paranoid theorists, searching for the ‘hidden hand’ behind the social and political insecurity infecting the continent. In the writings of the Abbé Barruel, an ex-Mason and priest who had escaped the Terror, and the Scotsman and scientist John Robison, Weishaupt’s humble and quite harmless Illuminati, which at its height numbered only a few hundred members, grew to gigantic proportions. Responsible not only for the French Revolution, it became a monstrous spectre, haunting Europe. Soon the idea that this secret, ruthless society was at work undermining the monarchies and elected governments of the world, took hold, and, with some variations, has maintained its grip on our modern political anxieties. Although the real history of the Illuminati is little known, Weishaupt’s spawn has become a cipher into which we read our own fears and uncertainties, as well as the stuff of sensational best sellers. The novelist Dan Brown, who achieved global fame with The Da Vinci Code – a thriller that taps the secrecy surrounding the mysterious Priory of Sion and the hidden ‘bloodline’ of Christ – scored another worldwide success with his novel Angels and Demons, in which the Illuminati plot to destroy the Vatican. Weishaupt would no doubt have approved of the plot, but would have found Brown’s pseudo-history of his society baffling.

Although the Illuminati pose no real threat and, most likely, do not exist – regardless of the many internet sites devoted to uncovering their evil designs – the idea that some hidden mastermind is behind the scenes, making decisions that affect our lives, has become a part of postmodern consciousness. In a world in which our experience, and the information we use to understand it, is increasingly filtered through a variety of electronic media, the idea that “nothing is true, and everything is permitted” is seen to be less and less improbable. In our age of Al Qaeda, Wikileaks, the Bilderbergs, and other mysterious powers, the individual is increasingly thrown back on his own resources in order to arrive at some idea of truth. If, as many of the followers of secret societies maintain, the everyday world we take for granted is somehow false, then perhaps this is a good thing. We all then must find some way to make sense of what is happening around us. How each of us do this is up to us, and perhaps it is best if we keep that – secret.