This is the text of a talk I gave at the Center for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona in May of this year, on the links between art and the occult. As I point out in the talk, this connection goes far back into our past and seems to have been on hand when human consciousness first arose out of its animal roots and became aware of itself and the strange world in which it had awoken. From there I chart some of the main points of contact between the artist and the occultist or magician, until we arrive at our own recent re-discovery of the occult by artists bored to tears with postmodern irony and apathy and the self-censoring requirements of producing work that is socially useful. One expression of this search for something more than ironic self-reflection or social utility is what has come to be known as “occulture,” and at the end of the talk I mention some current efforts to get this across to a, with any luck, eager audience. Here is a link to my talk. And here it is in pixels.

Seeing the Invisible: Art and the Occult

In recent years the occult, the mystical, and the magical have become popular subjects in the art world, but the links between art and the occult reach back much further than we think. The earliest signs of art appear at the very start of our humanity, and even then it was associated with other worlds. 40,000 years ago, during the Upper Palaeolithic, humans like ourselves used art as a means of entering other realms and as a way of recording what they encountered there. Cave art found in places like Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain suggest that our prehistoric ancestors used these interior spaces to enter another “inner” world, that of the mind, or, as they more likely would have thought of it, the spirits.

While in trance states - most likely induced by psychedelic substances - prehistoric artists made cave paintings depicting the strange half-animal, half-human creatures they encountered, what are known as “therianthropic figures.” Some theorists suggest these cave paintings later became symbols prehistoric psychonauts meditated on while within these deep spaces.[1] As the hallucinogens altered their consciousness, our ancient ancestors performed rituals and offered prayers to the spirits evoked through the images on the walls. Like later shamans, these early visionaries returned from their inner journeys with helpful knowledge gleaned from the other side. It seems that from the start, the insight that “in art it is necessary to study ‘occultism’” and that the artist “must be clairvoyant; he must see that which others do not see” – as the esoteric philosopher P. D. Ouspensky, whose writings influenced Russian avant-garde artists like Kasimir Malevich and Mikhail Matiushin declared – was in full force.[2]

Architecture in its earliest forms was also concerned with realities beyond the everyday. The earliest dating for the construction of Stonehenge, the most famous megalithic site, is 3100 BC. While perhaps not strictly “art,” the precision with which the enormous stone slabs making up Stonehenge are arranged induces an unquestioned aesthetic effect, which must have played a part in whatever other purposes the site may have served. Many theories suggest why our Neolithic ancestors erected these gigantic blocks, some of which weigh up to twenty-five tons, ranging from the needs of human sacrifice to a landing base for UFOs. Yet many researchers agree that, like other megalithic sites, these massive stones were placed with an accuracy modern engineers would find difficult to match, in order to chart the movement of the sun, the moon, and the stars. Yet these astronomical calendars were not erected simply to record the change of seasons. As the writer Colin Wilson suggests, our ancient ancestors seem to have had some intuitive awareness of a kind of energy coming from the heavens and the earth itself, and they constructed Stonehenge in order to mark the times when this mysterious occult power was most present.[3]

Later, more sophisticated structures, like the great pyramids of Giza, seem to have been made with a similar aim, and suggest that whoever was responsible for them had a knowledge of astronomy and earth science far in advance of what conventional thought allows. There is considerable evidence that during their construction the pyramids served as observatories and that the accuracy with which they were able to pinpoint distant stars had more to do with ideas about the afterlife than with the demands of agriculture. While it is clear that later pyramids did serve as tombs, nothing about the great pyramids of Giza suggests they served as monumental mausoleums. There is reason to believe they served as initiatory temples, within which priests mastered the art of separating the soul from the body, so that it could begin its journey to the stars.[4] The very shape and contours of these spaces are believed to have been designed in order to create specific states of consciousness.

The pyramids are thought to contain much esoteric, occult knowledge. This is perhaps even more true of the Sphinx, which some believe predates the pyramids by millennia. According to the 20th century spiritual teacher G. I. Gurdjieff, the Sphinx is an example of “objective art,” which is designed to have the same precise effect on every viewer, unlike our more “subjective” art, which aims to express an idea or feeling of the artist, and about which the individual viewer can decide for himself.[5] We do not know who constructed the Sphinx or who is responsible for the strange sensation it still produces in those who stand before it. The same is true of the nameless stone masons and carvers who built the Gothic cathedrals.

In a highly competitive market, it is important for artists to have their name known. This was not the case during the rise of the Gothic (AD 1150-1220). Artists then did not ascribe their work to themselves; they rather lost their “selves” in the service of something greater. Some have suggested that those responsible for the cathedrals of Chartres and Notre Dame de Paris belonged to esoteric “schools,” part of whose work was to embody in stone occult secrets about man, God, and the cosmos.[6] According to the mysterious 20th century alchemist Fulcanelli, the bas-reliefs, decorations, images, and icons depicted on the stones of Gothic masterpieces, speak the strange language of argotigue, which communicates alchemical secrets to those who can read it, and hides them from those who cannot.[7] As in the great Egyptian structures, one can detect the effect of “sacred geometry” in these holy places, the conscious use of the Golden Section and other significant measurements, derived from ancient sages like Pythagoras and Plato. When combined with the vivid stained glass of their enormous rose windows and early polyphonic music, the otherworldly effect within places like Chartres must have been transformative, sending their congregations into communal altered states.

In the sense that we know it, art comes into its own in the Renaissance. Here too we find the influence of the occult. The Renaissance was, of course, about rediscovering the works of ancient sages like Plato, lost for centuries. But as the historian Frances Yates makes clear in Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, the Renaissance was even more about the rediscovery of the works of the most famous magician of all time, Hermes Trismegistus, “thrice greatest Hermes.” In 1463, a book scout for the Florentine power broker Cosimo de’ Medici came across a collection of Hermetic texts, believed to have been written by the great magician himself. Marsilio Ficino, Cosimo’s scribe, was busily translating some lost works of Plato when Cosimo pulled him away to work on Hermes instead. The result was a remarkable infusion of Hermetic and occult ideas into the burgeoning Renaissance genius. This can be seen in Botticelli’s Primavera (1482) the painting of which Yates suggests was directed by Ficino and which she describes as a “practical application of magic, a complex talisman.”[8] Sculpture too was informed with the Hermetic vision; as Yates writes: “The operative magi of the Renaissance were the artists and it was a Donatello or a Michelangelo who knew how to infuse the divine life into statues.”[9]

By the early seventeenth century, through an intolerant church and a rising modern science, the Hermetic teachings, hitherto respected, had lost much of their prestige. Yet this was a time when occult art flourished, in illustrated alchemical texts and “maps” of the hidden worlds, what was known as “hyperphysical cartography.” These complex diagrams made of colourful concentric circles, triangles, text, and striking illustrations depicted the secret relations between the physical and spiritual worlds. Alchemical works were crowded with red dragons, green lions, hermaphrodites, suns, moons and other strange symbols, many of which Surrealism would later borrow, conveying to the initiated the inner workings of nature. One of the most remarkable of these works was Michael Maier’s Atalanta Fugens (Atalanta Fleeing) which appeared in 1618 and is an early example of multi-media, combining poetry, images, and music to convey the alchemical meaning of the ancient Greek myth.

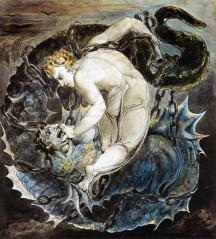

As science and rationalism drove the Enlightenment on, many artists, wary of the new clockwork universe, rebelled and turned instead to the strange, the unusual, and the uncanny. The new ordered world seemed cold and barren, and they sought inspiration in the mysterious and in visions of a more romantic past. The Gothic revival bred a taste for ruins and desolate places, and for the darker side of human nature. The supernatural, left out of the Enlightenment agenda, was a favourite theme, and Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781) expresses the fascination with the hidden, repressed, occulted self. Fuseli was one of many artists, writers and thinkers making up the “occult underworld” of late eighteenth century London; another was Fuseli’s friend, the poet, painter, and visionary William Blake, who himself attended séances.[10] Blake, an engraver, was practically unknown as a poet and painter during his lifetime. Yet Blake’s paintings, full of Michelangelesque men and women and bursting with vibrant vital forms and colours, are now treasured and are recognized, along with his poetry, as expressions of his spiritual, Hermetic vision. As Kathleen Raine points out, Blake was not an untutored “mad” genius. He was well schooled in the Hermetic philosophy, and as is the case with many Renaissance masterpieces, his striking paintings, engravings, and illuminated texts – another example of mixed media – are filled with symbols and images relating to the esoteric tradition.[11]

In the nineteenth century the Romantic rejection of the rising modern world spread across Europe and took root very firmly in Germany, as the eerie otherworldly paintings of Caspar David Friedrich show. Friedrich’s haunting landscapes, depicted in almost hallucinatory detail, leave the viewer with the sense of some other world, shimmering behind nature’s surface. This suggestion of a different reality, just out of reach, would inform the Symbolism that emerged as the century drew on. Rooted in the visions of the Swedish scientist and religious philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg and his belief in a correspondence between the things of this world and the realities of a higher one, Symbolism informed the literature, art, and music of the time, reaching into Baudelaire’s poetry, Wagner’s operas, and the work of painters like Gustav Moreau and Odilon Redon. Orpheus, the poet-mystic of Greek legend, who descends into the underworld, was a favourite subject of Moreau’s lush, exotic works. Redon’s dark visions are best seen in his illustrations for Gustav Flaubert’s hallucinatory novel The Temptations of Saint Anthony (1874).

Redon was a familiar face in the mystical underground of fin-de-siècle Paris, where he rubbed elbows with other artists interested in the occult, such as the composers Erik Satie and Claude Debussy, the poet Stéphan Mallarmé, and the novelist J. K. Huysmans, whose Là-Bas (1891) is a classic of decadent Satanism. Important at this time was the occultist “Sar” Merodack Péladan, who initiated the famous Salon de la Rose-Croix, where, in 1892, Satie premiered his Trois Sonneries de la Rose +Croix. It was in this milieu that René Guénon, the founder of Traditionalism, and René Schwaller de Lubicz, the maverick Egyptologist and alchemist, began their careers. Inspiring the fin-de-siècle obsession with the occult were the thrilling works of the French magician Eliphas Levi, himself a skilled draughtsman, whose readers included Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and many others. In Dogme de la Haute Magie (1854) Levi argued that the most powerful weapon in a magician’s arsenal was his imagination, an insight that later magicians, like the notorious Aleister Crowley, no stranger to the canvas himself, developed considerably.[12]

Ironically it was in the stridently “modern” twentieth century that art’s links to the occult really came into their own. In 1912 Wassily Kandinsky published On the Spiritual in Art (1912), a work predicting a coming “Epoch of the Great Spiritual.” Influenced by his reading in Theosophy and Rudolf Steiner, Kandinsky saw art as a spiritual counterblast to the increasing materialism of the age. Kandinsky was not alone. Other important modernists, like Frantisek Kupka and Piet Mondrian were also inspired by their reading in Theosophy. Where Symbolism suggested another world, somehow hovering behind this one, Kandinsky and the others saw art as a means of entering that world itself, of reaching directly into the higher dimensions. Kandinsky is credited with having created the first abstract painting, but that distinction may really belong to an artist who was unknown at the time, but whose work, because of the recent interest in “occult art,” has come to light.

This was Hilma Af Klint, a Swedish student of theosophy and anthroposophy who is believed to have created an abstract work earlier than Kandinsky. One reason af Klint’s importance has been noted only relatively recently is that she did not exhibit her esoteric art in her lifetime, and asked that it not be shown to the public until twenty-five years after her death. When it was finally shown, more time than that had passed. Another is that, perhaps even more than Kandinsky, af Klint’s paintings were a means of entering into and exploring another level of reality.

Af Klint started out as a conventional painter, but her deeper interests were anything but conventional. Along with spiritualism, mediumship, automatic writing and painting, and other occult, mystical practices, she was also a student of Annie Besant and Rudolf Steiner. Working with other female artists also interested in the spiritual worlds, af Klint produced automatic works inspired by higher intelligences, that predate Surrealism by decades, and produced “abstract” paintings in advance, as said, of Kandinsky, Kupka, and Mondrian. But her interest in abstract art for its own sake was negligible. Her paintings were more overtly works of gnosis than art. That is, they were ways of knowing reality, of entering spiritual worlds and seeing the invisible. But in these areas these pursuits more often than not overlap. And for the esoteric artist, art is a way of knowing.

Hilma af Klint came to the attention of a wider public in 1986 when her work received its first major showing as part of the ground breaking exhibition, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and which I had the great fortune to attend. Curated by Maurice Tuchman, the exhibition filled the museum’s new wing with more than 200 works displaying in a variety of ways the influence that occult, mystical, and spiritual ideas had on modern art.[13] We can say that it was the mother of all “art and the occult” exhibitions, and that this one, here today, has its roots in that exhibition, more than thirty years ago.

Another female occult artist whose work has been rediscovered, mostly through the interest shown in af Klint, is Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884). Throughout the 1860s and ‘70s, Houghton produced a series of remarkable “spirit paintings,” nearly abstract water colours guided by angelic intelligences, as well as by some of the Renaissance masters. Houghton was a well-known medium in Victorian spiritualist circles, but her attempt to spread the acceptance of spiritualist art was a disaster – her exhibition in 1871 left her bankrupt - and like af Klint, she withdrew her work from public showing, although it is now getting much belated attention.[14]

A more successful, at least at first, occult artist was the Londoner Austin Osman Spare (1886-1956), who burst on the English art scene as an enfant terrible of the Edwardians, having received acclaim at seventeen in 1903 as the youngest ever exhibitor at the Royal Academy. Yet Spare’s celebrity was soon overshadowed by his interest in the occult, magic, and strange, liminal states of consciousness, and he quickly slipped into obscurity.[15] He developed an art of Beardsleyesque delicacy and magical power, creating an original system of sigils and occult signs, aimed at contacting other planes. Among his many occult influences was witchcraft, a muse he shared with the Australian painter Rosaleen Norton (1917-1979), whose pagan, demonic canvases are often similar to Spare’s.

Spare was for a short time an associate of Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) , mentioned earlier, the most notorious magician of the twentieth century, whose ideas influenced Norton and practically every occult artist that followed. Crowley himself painted, and in recent years his crude, disturbing work – like Spare and Norton, Crowley incorporates much transgressive sex in his occultism - has garnered much attention and been exhibited widely.[16] And with Crowley we enter a realm of occult art in which the distinction between magic and art, ritual and performance, always flexible, becomes practically non-existent, an in-between sphere known as “occulture.”

The roots of occulture, like that of most art movements, reach back in various directions, but we can say that one sure source for it was the remarkable resurgence of widespread popular occult interest that made up the “occult revival of the 1960s.” World War I had put an end to fin-de-siècle occultism. Interest in spirituality and the occult rose again in the post-war years and we can even see the 1920s as a kind of ‘golden age of modern esotericism,’ with many of its major figures all operating at the same time. And, as I briefly mentioned, Surrealism had more than a passing interest in the occult, André Breton himself being especially fascinated by the Tarot. But by the ‘dirty thirties’ and World War II, attention had turned elsewhere.

Yet by the late 1950s, interest in magic, witchcraft, the paranormal, and especially UFOs, began to spread. The Beat poets of San Francisco and New York had discovered the wisdom of the East, in the form of Hinduism, Zen Buddhism, and the novels of Hermann Hesse. Colin Wilson’s The Outsider sent many off on existential quests. And in 1960, a book appeared in France that sparked an international magical revival. The Morning of the Magicians was a bestseller in France, and repeated its success in its English and other translations. Devoted to alchemy, ancient civilizations, extra-terrestrials , occult Nazis, mutants, and dozens of other strange ideas, in the Paris of Jean Paul Sartre and l’engagement it was as if a flying saucer had landed at the Café Deux Magots. A flood of books, films, television shows, and comic books, all riding on the occult wave dominated the popular culture of the time. By the middle of the decade, ideas that had been of interest to only a fringe segment of society, were now being embraced by the most famous people in the world, the Beatles. The rise in popularity of mind-altering substances like cannabis, magic mushrooms, and most influentially, LSD, seemed to confirm that a strange shift had happened, a return to ancient wisdom, smack in the middle of the modern age. It seemed that as man put his footprint on the moon, a new age of harmony and understanding was beginning on earth.

Yet by the early 1970s, that vision had faded and the dream dissolved. A grimmer sensibility settled in, a harder take on reality, a blacker shade of dark, that was reflected in popular culture. This was beginning of what we can call “dark rock,” the occult inspired current of heavy metal, and the more sophisticated enchantments of artists like David Bowie, who, like others, sought a golden dawn. And it was out of this in-between world, where art and magic meet, that occulture was born.

Allegedly coined by the performance artist/occultist Genesis P-Orridge in the 1980s, and associated with the high randomness of “chaos magick,” the portmanteau “occulture” gained academic credibility in 2004 when Professor Christopher Partridge defined it as a concern with “hidden, rejected and oppositional beliefs and practices associated with esotericism, theosophy, mysticism, New Age, Paganism,” and other ideas belonging to the “occult subculture.”[17] This elucidating mouthful reminds us that an academic discovery of the occult – or rediscovery, as many pre-Enlightenment scholars were well acquainted with it – coincides with its recent artistic reassessment. This has led to scholars, artists, and practitioners rubbing magical elbows at such events as the conference on “The Occult and the Humanities” held in 2013 by the art department of New York University and which featured artists, mages, and academics deliberating on the place of the occult in today’s culture.[18]

As you might expect, occulture covers a wide spectrum, ranging from the diaphanous watercolours of the contemporary Swedish artist Fredrik Söderberg, to the more aggressive displays of the Swiss mixed-media artist Fabian Marti.[19] It’s roots lie in earlier occult artists such as the Crowleyan filmmaker Kenneth Anger, and the equally Crowleyan actress and painter Marjorie Cameron (1922-1995) , in the cut-ups of William S. Burroughs Jr. (1914-1997) and Bryon Gysin (1916-1986), the magical cinema of Alejandro Jodorowksy and the dark “roccult and roll” of Orridge’s Thee Temple Ov Psychic Youth and similar acts.[20] Like most esoteric terms, occulture is open for multiple interpretation, and we should not expect it to sit quietly with any single one. According to the “subcultural entrepreneur” Carl Abrahamsson, we should see occulture as a “general term for anything cultural yet decidedly occult/spiritual,” a brief that certainly covers a lot of ground, and allows artists to explore something other than their deadpan apathy –as postmodernism demands - and gives occultists a new way to look at their interests.[21]

If nothing else, occulture has stirred up a lot of action, at least in the English speaking world, from lavishly produced publications such as Fulgur Esoterica’s Abraxas: International Journal for Esoteric Studies, Abrahamsson’s Fenris Wolf, Mark Pilkington’s Strange Attractor Journal, and William Kiesel’s Clavis: Journal of Occult Art, Letters, and Experience, to collectable texts from Scarlet Imprint, Jerusalem Press, and the Ouroboros Press. And there are the conferences, seminars, symposia, book launches, lectures, exhibitions and events, much like this one, that proliferate like errant spirits, let loose by some sorcerer’s apprentice. For something unseen, it seems pretty clear that the occult, at least in the art world, is getting a lot of attention.

[1] David Lewis-Williams The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002)

[2] P. D. Ouspensky Tertium Organum (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981) p. 133.

[3] Colin Wilson Starseekers (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1980) pp. 26-27.

[4] See, for example, Jeremy Naydler, Plato, Shamanism, and Ancient Egypt (Oxford, UK: Abzu Press, 2005).

[5] P. D. Ouspensky In Search of the Miraculous (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1949) p. 27.

[6] Rodney Collin The Theory of Celestial Influence (London: Watkins Books, 1980) p. 241.

[7] Fulcanelli Le Mystère des Cathédrals (Las Vegas, Nev. Brotherhood of Life, 2005) p. 42.

[8] Frances Yates Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1971) p. 77

[9] Ibid. p. 104.

[10] For a vivid account of this time see Marsha Keith Schuchard Why Mrs. Blake Cried (London: Century, 2006).

[11] Kathleen Raine William Blake (London: Thames and Hudson, 1970).

[12] For some interesting articles on Crowley’s paintings, see Abraxas International Journal of Esoteric Studies issue 3 Spring 2013 pp. 43-83.

[13] For more on the link between art and the occult, see my article “Kandinsky’s Thought Forms: The Occult Roots of Modern Art” at https://www.theosophical.org/publications/1405

[14] http://courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/what-on/exhibitions-displays/georgiana-houghton-spirit-drawings

[15] See Phil Baker Austin Osman Spare The Life and Legend of London’s Lost Artist (London: Strange Attractor Press, 2011).

[16] See Abraxas: International Journal of Esoteric Studies Issue 3 Spring 2013 for several interesting articles on Crowley’s painting.

[17] Quoted in Here to Go: Art, Counter Culture, and the Esoteric ed. Carl Abrahamson (Stockholm: Edda Publishing, 2012) p. 7.

[18] See my article “Occulture Vultures” in Fortean Times No. 310 January 2014 pp. 56-57.

[19] See my Introduction to Söderberg’s Haus C G Jung (Stockholm: Edda Publishing, 2013), a collection of water colours based on Jung’s home and my contribution to Fabian Marti and Cristina Ricupero’s Cosmic Laughter No. 1 Time-Wave Zero, Then What? (Berlin: Sternberg Press, Ursula Blickle Stiftung, 2012).

[20] My books Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius (New York: Disinformation Company, 2003) and Aleister Crowley: Magick, Rock and Roll, and the Wickedest Man in the World (New York; Tarcher/Penguin, 2014) explore the influence of the occult, particularly Crowley, on popular culture.

[21] Carl Abrahamson Resonances (London: Scarlet Imprint, 2014) p. 156.