This is the text of a talk I gave recently for the Marion Institute, part of their Living in the Real World seminar. The event was a great success, and the other speakers, Ptolemy Tompkins and Mark Booth, both gave excellent talks. The aim was to present ideas about different ways of living in the world, ones closer to what reality is really like, rather than the ubiquitous misrepresentation of it common to our time.

Rejected Knowledge:

A Look At Our Other Way of Knowing

This evening I’m going to look at a tradition of thought and a body of ideas that the historian of the occult James Webb calls “rejected knowledge.” I’m going to see if we can arrive at answers to four questions:

What is this tradition?

Why is it “rejected?”

Why is it important?

What does it mean for us?

Now before I start I’m going to ask you all to engage in a bit of philosophy. I’m going to ask you to perform a simple but very important philosophical exercise. This is something called “bracketing,” and it was developed in the early twentieth century by the German philosopher Edmund Husserl. Husserl is important for founding a philosophical school and discipline called phenomenology. We needn’t know a great deal about it and I’m not going to burden you with a lot of history or definitions. Put briefly, Husserl was scandalized by the mess that western philosophy had gotten itself into by the late nineteenth century and as he loved philosophy – he was obsessed by it – he thought the best way to proceed was to start from scratch. Now, I should point out that wiping the slate clean and starting from scratch is a well-tested tradition in philosophy, so Husserl was not doing anything radically new. But then, in another sense he was.

Phenomenology is essentially a method of describing phenomena, which means the things that appear to us, whether physical objects in the outer world, or my thoughts, images, feelings and so on that seem to reside in my inner world, my mind. If you look a tree, that is a phenomenon, and if you then close your eyes and imagine the tree, that is a phenomenon too. Both are objects that are presented to consciousness, and Husserl was interested in how phenomena present themselves to consciousness, and what role our own minds have in this presentation.

What Husserl suggested is that to begin this study, what we need to do is put aside everything we think we know about our object of observation. So if you were in his class and you were given an object to observe – say a book, a flower, or a chair, it doesn’t really matter – he would say “Don’t tell me what it is; tell me what you see.”

Now for any philosophers in the audience I admit I am simplifying things very much, but for what I am going to ask you to do that is all we need. The method of putting aside everything we think we know about something is what Husserl called “bracketing.” Basically it means to put aside your presumed knowledge of whatever you are observing, and place it in brackets. Placing it in brackets means that you don’t reject your knowledge, you don’t deny it or change your mind about it. You simply put it aside for the duration of your phenomenological work. You take it out of the equation for the time being. You don’t throw it away. You simply pick it up as it were and put it over there for a time. It was in this way that Husserl wanted to arrive at what he called a “presuppositionless philosophy,” basically a philosophy that begins without any preconceived ideas.

Now what I’d like you all to do is to become phenomenologists for a short while, at least for the duration of this talk. I’d like you to “bracket” everything you think you know about the world, about reality, about the universe and our place in it. Again, I’m not asking you to forget this or to reject it or to deny it. I am simply asking you to put it aside for a short while. In Husserl’s case this usually meant putting aside questions about the “reality” of something, about whether it was “true” or not, about its “essence,” and any “explanations” that could account for it, whether materialist ones or idealist ones. Phenomenologists don’t ask those questions, at least not at the beginning. What they try to do is describe the objects of consciousness and get some idea of what is involved in how they appear to us.

What this exercise is supposed to do is to make whatever you are observing “strange,” “unfamiliar,” “unknown,” “mysterious.” One definition of philosophy that I like very much and which can apply to our exercise here in “bracketing” is that it is “the resolute pursuit of the obvious, leading to radical astonishment.” Because one outcome of a successful exercise in “bracketing” is that it transforms something you believed you knew very well, into something quite mysterious. Something, perhaps, that surprises you.

So, let’s see if we can all be phenomenologists for a short time and temporarily put aside everything we know about the world we live in and our place in it. This means bracketing the Big Bang, Darwin, and all the scientific explanations about the world that we’ve been offered over the years, about atoms and electrons and Higgs-bosons and selfish genes and DNA and so forth. Take all of that and put it in brackets.

Okay? Have we done that? Good.

The tradition of rejected knowledge that I’m going to talk about is what we can call the Hermetic tradition, or the Western Inner Tradition, or the Esoteric Tradition, or the Occult tradition. I should point out that “Hermetic” comes from the teachings of Hermes Trismegistus, the mythical founder of philosophy and writing, about whom I’ve written a book, The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus. Esoteric means “inner” and occult means “not seen.” Each of these names has a very specific sense but in a broad, general application they all refer to the same thing. They refer to a body of ideas and philosophies and spiritual practices that were for many centuries held in very high regard in the west, but which in the last few centuries – since the rise of science in the 17th century – have lost their status and been relegated to the dust bin of history. They are rooted in several what we can call mystical or metaphysical philosophies and religions of the past, Hermeticism, Gnosticism, Kabbalah, neo-Platonism and related belief systems. We needn’t know exactly what these are now and we’ll try to get some idea of some of them as go along. We now think of these things and the practices associated with them as superstitions, as myths, more or less as nonsense. I’m thinking of things like astrology, alchemy, magic, mysticism, the Tarot, or of experiences like telepathy, precognition, out-of-the-body experiences, of mystical experiences, of feelings of oneness with nature, with the cosmos, of what we can call “cosmic consciousness,” of belief in life after death, in consciousness existing outside the body, of astral travel, of visionary experiences, of contact with angels and other spiritual beings, of strange states of mind that lead to sudden, accurate knowledge of and insight into the workings of the universe, and into the mystery of our own being, of dimensions beyond space and time, of the experience of the soul and the spirit.

Experiences of these and similar things and a real knowledge about them were for very many centuries accepted by both men and women of learning and also by the everyday people, the common folk. These people lived in a world in which such things were possible. More than this, they lived in a world in which such things were considered of the highest importance. Much more important than the everyday, physical world they inhabited. That has gained a supreme importance only in the last few centuries, and it has gained this importance through diminishing the importance of what we may call the “spiritual” or “invisible” side of reality. We’ll return to this shortly.

To give you an idea of how important this tradition of thought was considered, let me mention a few of the people who believed in it and occupied themselves with it.

Given that he is considered the father of modern science and the modern world in general, it is surprising to know that Isaac Newton, probably the greatest scientific mind in western history, was a passionate devotee of this tradition. Newton wrote more about alchemy than he did about gravity. Gravity itself is an “occult” force. “Occult” simple means hidden, or unseen, and as far as I know, no one has seen gravity. Newton’s investigation into the physical laws of the universe – that have allowed us to put men on the moon and probes out into the deepest regions of space - emerged from his life-long interest in alchemy, in understanding the secret meaning of the Bible and, like Stephen Hawking in our own time, knowing the “mind of God.”

Thomas Edison, the inventor of the light bulb and much else, was an early member of the Theosophical Society, the most important occult, esoteric or spiritual society in modern times, founded in New York in 1875 by that remarkable Russian emigre, Madame Blavatsky. Along with all the other inventions he is known for, Edison was very interested in “spirit communication,” and for a time he worked on developing a way of recording messages from the “other world.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was deeply involved in Freemasonry, a society that in its early years was profoundly informed by Hermetic, esoteric ideas. Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, is a kind of initiation ritual in music. Beethoven was also interested in Freemasonry as was Franz Joseph Haydn and several other famous classical composers. I might also mention that the earliest operas were based on alchemical ideas. I should also mention that it is well-known that George Washington and other of America’s founding fathers were Masons.

William James, the great American philosopher and psychologist, and one of the great teachers at Harvard, had a powerful interest in mystical experiences – so powerful that he experimented with nitrous oxide in order to have one himself. He was also deeply interested in the paranormal and he investigated several mediums. His friend, the French philosopher Henri Bergson, a Nobel Prize winner and for a time the most famous thinker in the world, shared James’ interest and was a president of the Society for Psychical Research.

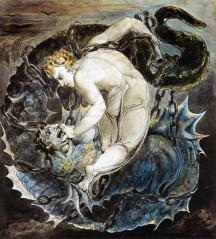

Many poets and writers and artists were very keen on this tradition of “rejected knowledge.” The German poet Goethe practiced alchemy. W. B. Yeats – another Nobel prize winner - was a Theosophist and also a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, one of the most important occult societies of modern times. The Swedish dramatist August Strindberg was an alchemist too and also a great reader of the Swedish mystical thinker Emanuel Swedenborg. I should mention that Johnny Appleseed, the early American ecologist, was also a devotee of Swedenborg, as was the poet William Blake, who saw angels as a child and had conversations with spirits and inhabitants of “other worlds” throughout his life.

The Renaissance, the revival of classical thought that took place in the 15th century and produced some of the most treasured works of art in the western world, works by Michelangelo, Botticelli, and others, was saturated in Hermetic, esoteric thought. The Renaissance is generally seen as a time when the works of Plato and other Greek philosophers were re-discovered after being lost for centuries. But it was even more a time when the ancient teachings of Hermes Trismegistus, thrice-greatest Hermes, the founder of magic and writing, were rediscovered after being obscured for a millennia.

Some of the early church fathers were followers of some aspects of this tradition and before them Plato, the greatest philosophical mind of the west, was, if not a devotee, certainly a fellow traveller, and we have reason to believe that much of Plato’s philosophy was informed with ideas and insights gathered from this tradition.

This list could go on. I mention these names here just to show that, although this tradition is “rejected” by modern thinking, some of the most important figures in science and the arts embraced it whole-heartedly. This, of course, doesn’t prove anything, but it does suggest that if world-renowned scientists, Nobel Prize winners, influential poets, musicians, and philosophers – and again, this is just a fraction of the important people with an interest in this tradition – had the time for it and devoted much energy and thought to it, it must have something going for it. Or should we accept that Newton and Mozart and Goethe and the others were simply “superstitious,” weak-minded, gullible characters who were simply not as smart as modern sceptics ,who consider the tradition these men of genius felt themselves to be a part of sheer nonsense?

I don’t know about you, but I hesitate to call Newton or Goethe or Mozart weak-minded and gullible. So if they weren’t, why were they interested in something we in the modern world reject?

This leads me to my second question: why was this tradition rejected? And who, exactly, rejected it?

The short answer is that it was rejected because of the rise of science, which began its road to dominance in the 17th century. The story is actually more complicated than that and involves the church and the rise of humanism, an outgrowth of the Renaissance, but for our purposes it is sufficient to contrast the way science sees the world with the way the rejected tradition sees it. Or, I should I say, the way in which science knows the world and the way in which the rejected tradition knows it. Because fundamentally, this is the issue. All of the different philosophies and teachings that are rooted in the rejected tradition – magic, alchemy, astrology, mysticism and so on – all share in common a particular way of knowing the world. And it was this “way of knowing” that science, or what became what we call “science,” rejected, along with the knowledge accumulated through that knowing.

Now as “knowing” is something we do with our minds, it is something directly related to our consciousness. Knowing is an activity performed by a consciousness, whether yours, mine, an alien’s, or, perhaps, an intelligent machine’s.

One of the things that Husserl and other phenomenological philosophers discovered is that different kinds of consciousness, or different modes of the same consciousness, can “know” things in different ways. Conversely, they also discovered that they can also know different “things.” We can see this from our own experience. I know, say, my name, what the product of 2×2 is, and also how to ride a bicycle. But I know these in different ways. I know my name because at some point someone told me what it was, and by now I have accumulated boxes of documents confirming this. I know that 2×2=4 because logic and reason tell me it does. Try as I may to “know” that 2×2=5, I can’t because it doesn’t. Of course, I can be coerced into agreeing that 2×2=5, as the people in Orwell’s 1984 are, but this isn’t really knowing. And I know how to ride a bicycle because, after many failed attempts I finally “got the knack” of doing it. But if you try to tell someone how it is done, as if in a step-by-step manual, you will find that it is not so easy to do. I can show someone how to do it, but to give a clear and adequate account of how I do it is actually quite difficult.

Another example. I mentioned Mozart, Beethoven and other composers. I know that Beethoven’s late string quartets are about something deeply moving and profound, but I would find it just as difficult to say what they are about as I would if I tried to tell someone how to ride a bike. I can’t say exactly what the music is about, but I would also reject any account that said it was just vibrations of air, which, physically, is what the music is. It’s about something more than that, about something deep, profound, even mystical, but exactly what, I can’t say.

Or say you have a hunch or an intuition about something and are very certain it is important. A friend asks “But how do you know?” All you can say is “I don’t know, but I do!”

This other kind of “knowing,” the kind that recognizes something deep in music, or in poetry, or in works of art, or accepts intuitions and hunches, that knows with the gut, as it were, is, it seems to me, related to our rejected tradition.

Now what differentiated science – and again, let me say I know this is a huge generalisation, and let me make clear that I am no enemy of science, but of what we can call “scientism,” which is a kind of “fundamentalist science” in the way that we have “fundamentalist Christianity” or “fundamentalist Islam” – what made it different from earlier modes of knowledge and methods of acquiring it is that it focused solely on observing physical phenomena and, in a way, did its own kind of bracketing by forgetting any ideas about what might be behind the phenomena, making them happen. Roughly this meant jettisoning God, or the angels, or spirits, or soul, or any kind of purpose or mind at work in nature. It puts aside any theories or traditional ideas and just watched and saw what happened. This approach to understanding the world had its roots in the philosopher Aristotle, who was Plato’s pupil. But where Plato was interested in understanding what we can call the invisible higher realities behind or above the physical world – what he called the Ideas or Forms, a kind of metaphysical blueprint for reality perceived through the mind, not the senses – Aristotle did just the opposite. He devoted himself to observing the natural world.

Aristotle’s theories dominated the west for centuries but eventually were discarded. But between the two – he and Plato – we can see the different ways of knowing. Aristotle is the first “research scientist, “ collecting data and devising theories to account for why things are the way they are. Plato is much more interested in the higher reality of which the physical world is just a shadow. He often uses myth in his accounts and started life as a poet. Aristotle started the tradition of the unreadable philosopher. He also started systematic logic, in which A can only be A and never Not A and so on. For Aristotle, something is or it isn’t. There’s no middle ground. He sees an “either/or” kind of world rather than a “both/and” sort of one.

But along with paying attention to the physical world, which people had been doing all along, science brought to its investigation a powerful tool: measurement. It discovered that the forces at work in the physical world could be measured. Speed, mass, weight, acceleration, space, extension, and so on could be quantified. And what was remarkable about this is that with enough knowledge of these quantities, events could be accurately predicted. It is this predictive power of measurement that enabled men to get to the moon and space probes to shoot past Pluto. Needless to say this was truly an achievement and it has enriched our lives and the lives of our ancestors immeasurably – if you can forgive an atrocious pun. But one result of this is that it split the world in two, basically between the kinds of things that could be measured in this way, and the kinds of things that can’t.

The person who made this split official was Galileo. What Galileo said was that all the things that could be measured were primary phenomena. They were “really real,” and existed in their own right. They were objective. The other things were less real. They were subjective, which meant that they only existed in our minds, our psyches. So the brilliant, moving colors of a sunset are our subjective experience of the objective reality, which is wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation. Color, scent, texture, taste, are all subjective. They don’t exist on their own. We add them to our experience. But they don’t “really” exist, at least not in the way that the primary things, that can be measured, do. We can’t measure the awe and wonder we feel looking at the sunset, but we can measure the electromagnetic radiations we are being dazzled by.

This worked well for science. It gave it something hard and solid to hold on to. But this was at a cost. Because what we value in experience are precisely those things that science has told us for some centuries now are not real. The things that science can measure accurately and make effective predictions from are things that no one except scientists get excited about. And the kinds of things that thrill all of us, science has explained to us are only in our head. The world really isn’t beautiful. We see it that way. But it itself isn’t. Not really.

The other thing the new way of knowing did was to break things up into smaller and smaller bits and pieces, which were subject to cause and effect. There was no pattern holding things together, no “great chain of being,” no “web of life” or “whole” into which everything found its place. A world of atoms subject to physical forces could account for everything. The world really was a huge machine, a mechanical cosmos that needed no mind or intelligence or spirit or anything else to run, merely blind physical forces.

Now, what does all this have to do with our “rejected tradition?”

Well, the kind of knowing associated with that tradition is the polar opposite of the kind that made science so successful. And I should point out that science is successful because it is immensely helpful in our attempt to control the world. It has immense utilitarian and practical benefits. It gets results. It makes things happen. The kind of knowing associated with the other tradition isn’t like this. It isn’t practical or utilitarian in that sense. It isn’t a “know how,” more a “know why.” It’s a knowing that isn’t about controlling the world – which, in itself, is not bad, and absolutely necessary for our survival – but of participating with it, even of communicating and, as we say today, interacting with it.

Probably the most fundamental way in which these two kinds of knowing differ is that in the new, scientific mode, we stand apart from the world. We keep it at a distance, at arm’s length. It becomes an object of observation; we become spectators, separated from what we are observing. With this separation the world is objectified, made into an object. What this means is that it loses, or is seen not to have, an inside. It is a machine, soul-less, inanimate, dead. We object to this when it happens to us, when we feel that someone is not taking into account our inner world, our self, and is seeing us as an object, as something without freedom, will, completely determined. But it is through this mode that we can get to grips with the world and arrange it according to our needs.

Whether we are scientists or not, this is the way in which we experience the world now, at least most of the time. There is the world: solid, mute, oblivious, and firmly “out there.” And “inside here” is a mind, a little puddle of consciousness in an otherwise unconscious universe.

The mode of knowing of the rejected tradition is the opposite of this. It does recognize the “inside” of things. It does not stand apart from the world and observe it from behind a plate glass window. It participates with the world. It sees the world as alive, as animate, as a living, even a conscious being. And it sees connections, links among everything in this world. Where the new mode worked best by breaking the world down into easily handled bits and pieces that were best understood as subject to physical laws of cause of effect, the kind of knowing of the rejected tradition saw connections, correspondences among everything in the world, it saw everything as part of a total living whole. We can say that where the scientific mode works through analysis, the other mode works through analogy and synthesis. Elements of the world are linked for it not by mechanical cause and effect, but by similarity, by resemblance, by a kind of poetry, by what we can call living metaphors. Plants, colors, sounds, scents, shapes, patterns, the position of the stars, the times of day, different gods and goddesses, angels and spirits were woven together into subtle webs of relations, where each echoed the other in some mysterious way. In ancient times, this was known as “the sympathy of all things,” the anima mundi, or “soul of the world.” We can say that instead of wanting to take things apart in order to see what makes them tick – and the machine analogy here is telling – the rejected tradition wants to link them together to see how they live. And where the new way of knowing worked with facts and formulae, the other way worked with images and symbols.

The most concise expression of this other way of knowing is the ancient Hermetic dictum, “as above, so below.” This comes from the fabled Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, a work of alchemy attributed to Hermes but which makes its appearance round about the eight century AD. This means that there is a correspondence between the things in heaven and the things on earth. In one sense, this is understood as a correspondence between the position and movements of the stars and human destiny. This is astrology. But in a broader, more fundamental sense it means that man, human beings are a kind of microcosm, a little universe, and that we contain within ourselves vast inner spaces, that mirror the vast outer spaces in which our physical world exists. In the rejected tradition, the whole universe exists within each of us, and it is our task to bring these dormant cosmic forces and realities to life. If in the new, scientific tradition we have begun to explore outer space, in the rejected tradition we turn our attention inward and explore inner space. And just as they do on Star Trek, we find inside ourselves “strange new worlds.”

This is a very different picture of humankind than what we get with the scientific mode of knowing. There we are just another collection of bits and pieces pushed and pulled by a variety of forces, with no special role to play or purpose to serve. Physical forces, biological forces, social forces, economic forces have us at their beck and call. There is no universe inside us. Our minds are a product of purely material forces and are driven by physical needs and appetites.

The rejected tradition sees humankind as very different, as central to the universe, as the answer to the riddle of existence. And this is why it is important to understand its place in our history.

One of the consequences of the scientific mode of knowing is that it ultimately arrives at a meaningless, mechanical universe. This is why the astrophysicist Steven Weinberg can say that “the more the universe seems comprehensible the more it also seems pointless.” He is not alone in thinking this. With the rise of science and the decline of religion, the idea that there is any meaning to existence also declined. Science did not set out to arrive at a meaningless universe, but it was driven to do so by the force of its own logic. If the only “really real” things are the sorts of things that are amenable to measurement – basically, physical bits and pieces - then things like “meaning” or “purpose” and other “spiritual” kinds of things are not really real. And if the universe is pointless, then human existence must be too. There is no reason for our existence. Like everything else, we just happened.

This is pretty much what the accepted picture is in the modern world. For the past few centuries we’ve slowly become accustomed to the idea that life is ultimately meaningless. Science presents one version of this insight, and much of the literature and art and philosophy of modern times does too. A great deal of this sentiment is summed up in the existential philosopher Jean-Paul-Sartre’s remark, “man is a useless passion.” “It is meaningless that we live,” Sartre said, “and it is meaningless that we die.” Martin Heidegger says we are “thrown into existence.” Albert Camus talks of the “absurd.” These thinkers from the last century were at least troubled by these reflections and sought to arrive at some stoic endurance of fate, some meaningful response to meaninglessness. But today, in the postmodern world, we’re not fussed. Life’s meaningless? Okay. We’re lost in the cosmos? No biggie. We’ve been there and done that and got the tee-shirt. We have accepted as a given what the writer and philosopher Colin Wilson called “the fallacy of insignificance,” the unquestioned belief that each of us individually and humanity in general is of no significance whatsoever.

The problem with this is that such a bland acceptance leads to a cynical, shallow view of life. It reduces it to a bad joke. It makes it small, trivial, and shrinks everything to an anonymous, uniform, “whatever.” I don’t think it takes a great deal of observation to see that we have become addicted to trivia and are up to our ears in methods and techniques of distraction. We have become used to nihilism, to the idea that “nothing matters.” In many ways we like it, because it lets us off the hook. We no longer have to think about serious things or take ourselves seriously. And in a world in which there are no “spiritual” values, the only thing worth pursuing is material gain. Needless to say there’s quite a lot of that going on. But even that can only go so far. My own feeling is that soon even it will be seen to be pointless. What we will do after that to entertain ourselves is unclear, but I shudder to consider the possibilities.

I would also say that our pressing ecological, environmental, economic, social and other crises have their roots, ultimately, in this “fallacy of insignificance” in the lack of belief in any values other than material ones.

Now this rather bleak spiritual landscape is a result, I believe, of our overvaluing one way of knowing at the expense of the other. It is a result of our understandable over-appreciation of the new way of knowing. And I should make clear that I am not saying the new way of knowing is bad, or evil, or that we should get rid of it and return to the older way. Developing the scientific way of knowing was a true breakthrough and a necessary and indispensable part of the evolution of consciousness. But as I’ve tried to point out, it has its drawbacks. While a return to a pre-scientific time is neither possible nor desirable, what we can do is see if the rejected tradition can offer anything to even out the imbalance. Can we learn something from it to help us move through this rather uninspiring time? Can we salvage some of our “rejected knowledge” and see if it can inform us and help us make creative, positive decisions about ourselves and the world? Can we accept some of this knowledge so that it is no longer rejected?

Let’s take a look at it.

We’ve already seen that it sees the cosmos as living, even conscious, rather than as a dead, empty mechanism.

We’ve seen that it sees connections running throughout the elements of this cosmos, patterns, correspondences, analogies, sympathies, echoes, communication. Blake, a student of the Neo-Platonic tradition, wrote that “A robin redbreast in a cage puts all Nature in a rage.” There is the sense that everything is connected in some way with everything else, is in a way integrated. This would mean that the other mode of knowing sees the world as “dis-integrated,” as broken up, fragmented, as things jumbled up in a box rather than a whole.

It also recognizes realities that the other way of knowing does not. Invisible forces and energies, subtle influences, spirits and souls, but also values like beauty, truth, the good, the values that make up what the psychologist Abraham Maslow called the “higher reaches of human nature” and which we associate with a spiritual orientation to life, rather than a material one.

We have also seen that the other way of knowing enters into the world, rather than remaining detached from it. And this I think is the key thing to grasp. Because it is this through this kind of “participatory consciousness” that everything else follows. And it is something that we can experience for ourselves.

Probably the most difficult part of the rejected tradition that someone firmly convinced of the accuracy of the scientific picture of reality will have accepting, is its attitude toward consciousness. To put it simply, in the scientific, modern view, consciousness is a product of the material world. Whether it is neurons, electrochemical exchanges, or elementary particles, in some way consciousness is explained via some physical agent, and it is something that takes place exclusively inside our heads. I address this belief – for this is what it is – in my book A Secret History of Consciousness, where I look at several philosophies of consciousness which take a very different view. This other view is the polar opposite of the scientific one. In this view, consciousness is primary, and the physical world, the world “out there,” the world we are all inhabiting is in some way produced by consciousness. This means that you and I, right here and now, are in some way creating the world around us, are responsible for it. This is why the nineteenth century French Hermetic philosopher Louis Claude de Saint-Martin said that we should not explain man by the world, as material science tries to do, but the world by man, as the Hermetic, esoteric tradition does. This is also what is meant by the Hermetic belief that man, the human being, contains an entire universe within him, is a microcosm. Within his mind, his spirit, there are infinite worlds. The world we see here and now is only one of them. If you change consciousness, you change the world.

Perhaps you can see why at the beginning I asked you to perform an act of “bracketing.” Everything we have been taught throughout our lives has in one way or another told us the complete opposite of what I just said. We have grown up within what Husserl called “the natural standpoint.” I should point out that by “natural standpoint,” Husserl was not thinking of “nature,” or a “natural” way of living. He simply meant the accepted, the usual, the ordinary, the everyday, the unquestioned. When we open our eyes in the morning we see a world “out there” and we assume quite naturally that all our perception is doing is reflecting it, as a mirror would. We, ourselves, our consciousness, have nothing to do with forming or shaping or providing that world. It is “there” and we simply “see” it. Husserl believed that the first step in philosophy, in understanding ourselves and in achieving self-knowledge is to challenge this. He believed we needed to step out of the “natural standpoint,” which in effect means to make the world strange. Not by distorting it as, say, surrealism does, or altering it as, say, what happens when we ingest a mind-altering substance, or seeing it as threatening, as happens in certain abnormal mental states. But simply by withholding assent to what we have hitherto never questioned, by bracketing what we “know” about the world and trying to see it from a different perspective. This is the “resolute pursuit of the obvious” which leads, if done correctly, to “radical astonishment.” The most obvious thing in the world is the world itself and it is also obvious that we are just a part of it, like everything else. Husserl and, in its own way, the Western Inner Tradition, asks us to put this belief aside and to try to see things differently.

I should point out that Husserl was not a devotee of this tradition. He was a genuine Herr Professor working all his life in the academy on questions of logic, mathematics, and epistemology. What is fascinating to me is that the sort of shift in our focus of consciousness that he asks for is in many ways the same as required in the Hermetic, inner tradition. Both ask us to put aside certain habits of thought, for this is all that the “natural standpoint” and the most rigorous expression of it, the modern, scientific mode of knowing, are. They are ways of perceiving, of knowing, and of thinking that have been built up, arrived at, over time. This is not to devalue them in any way, merely to show that they have evolved. They are not simply “given” as natural. This suggests that other ways of perceiving, knowing, and thinking can also evolve. And this is where we come in.

One of the first effects of “making the world strange” in the way that Husserl suggests is that it makes “you” strange too. The consciousness that has stepped out of the “natural standpoint” and taken an active stance toward “the world” rather than a passive acceptance of it, becomes aware of itself in a way that it never does when remaining in the “natural standpoint.” It becomes aware of itself as an activity, as a source of action. It feels more lively, more alive, more present, and becomes aware that what it had believed up till then to be absolute fact may not be as absolute as it had thought. Most important, it becomes aware of itself as a willed activity. Not wilful, in the egotistic sense – along with everything else, the everyday self that is associated with “wilfulness” is bracketed too – but in the sense of feeling its own “participation” in the “world” – it, after all, is doing the bracketing. Up till then it had simply accepted “the world” as something “there,” with which it had nothing to do aside from passive reflecting it. It becomes more aware of “I” as a living, vital, experience. It understands what Buckminster Fuller said when he remarked that “I seem to be a verb.” It overcomes its “forgetfulness of being,” in Heidegger’s phrase, and “remembers itself” as the esoteric teacher Gurdjieff believed we all needed to do. (In light of what we said about a “dis-integrated” consciousness, “re-membering” seems particularly apt.)

There are moments when we already feel this kind of “participation,” although we mostly are not explicitly aware of it and don’t speak of it in this way. But the effect of great art, poetry, music, literature, natural beauty, love, religious and spiritual practices all tend toward making us more aware of our inner life. They widen us, expand our interior, give us glimpses of that inner universe the rejected tradition tells us resides within us all. They are the “peak experiences” that Maslow believed came to all psychologically healthy people, and what he meant by “psychologically healthy people,” were people who rejected the “fallacy of insignificance” and who strove to actualize the “higher reaches” of their nature, the aspects of human being that are the central concern of our rejected tradition. And I should point out that as we actualise these “higher reaches,” the world around us is actualized too. We no longer see it as something solely to exploit or to abuse, as a dead, oblivious, mechanism, but as something living with which we can develop a relation. We develop an attitude of care toward it, we become, as the title of one of my books has it, “caretakers of the cosmos,” rather than insignificant accidents produced randomly within it.

And just as our present consciousness has evolved out of earlier forms, a new consciousness, more aware of the kind of knowledge and knowing that informs our rejected tradition, can also evolve. I am of the opinion that this is happening already and has been happening for some time and that we, now, are in a very good position to help it along. We are the inheritors of both traditions, both kinds of knowing, and we can see where and how the two need to be balanced and integrated. This is precisely the theme of my latest book, The Secret Teachers of the Western World, a historical-evolutionary overview of the place of the rejected tradition within western culture. It is my sincere hope that our other tradition no longer remains rejected and that its teachers and what they have to teach remains a secret no longer.