Here is the text of the talk I gave for the Lectorium Rosicrucianum, in Calw, Germany earlier this month. Calw is the home town of Hermann Hesse, and Hesse readers will know that the title of this post comes from his novel Steppenwolf. Because of the Hesse connection, I geared my talk accordingly. A few slightly awkward moments occurred during the talk - which was ably translated by my excellent translator Isabel - because of the significance a glass of wine has in the story. My Rosicrucian hosts were tee-total, but humor, another factor in the novel, saw us through. The afternoon we spent the next day at the Hesse museum in Calw made up for any misunderstandings.

I had brought a new translation of Steppenwolf - picked up at a charity shop - in honor of my adolescent obsession with Hesse. I dutifully read it while in Calw, but I have to say I was put off by its “updating” of the language and so-called “corrections.” Changing the famous tag line “For Madmen Only,” to “For Mad People Only,” just didn’t work and smacked too much of politically correct editing. Mensch in Germany means “man” or “one”, not “male,” just as “man” in English does not mean “male,” but “one” or “human”, unless of course you are referring a particular man. (A lot of ink has been spilled and feathers ruffled over this misunderstanding.) I’m glad that the original English translation by Basil Creighton, with all its poetry and romanticism, is still available. I have a hard cover first edition of the English translation from 1929 that has served me well for the past thirty-five years or so (I got it at a second hand shop in Los Angeles in the early ’80s.)

On the way to Stuttgart Airport for my flight to London, I was treated to a special, exclusive tour of the Johanes Kepler Museum in Weil det Stadt. Kepler featured in my talk and although the museum is closed on Mondays, the curator very kindly opened up for us and gave us the royal treatment. I first read about Kepler’s fascinating if difficult life in Arthur Koestler’s The Sleepwalkers, a brilliant and very readable history of the early years of modern astronomy. We had a further enlightening experience as we enjoyed the guided tour of Tubingen, the university town that in the late eighteenth century numbered Hegel, Holderlin, Schelling and many other important Germany philosophers and writers among its inhabitants, given by friends of my host. Tubingen was also an important center for the original Rosicrucians of the the early seventeenth century. It was out of the “Tubingen Circle” that Johann Valentin Andreae, most likely responsible for much of the Rosicrucian Manifestos, emerged. I write about this in Politics and the Occult - which, incidentally, will soon be available in audio format. (I sent off the Introduction earlier this week.)

Here’s the talk. Some of the ideas I touch on in it will be discussed in the Nura Learning course on the Lost Knowledge of the Imagination starting on November 17.

Regaining the Lost Knowledge of the Imagination: A Talk for the Lectorium Rosicrucianum Calw, Germany 20/10/18

This afternoon I’m going to talk about what I call “the lost knowledge of the imagination.” But before I start I should say that the phrase itself comes from the English poet and essayist Kathleen Raine. For many years Kathleen Raine guided the Temenos Academy in London, an alternative learning establishment whose aim was to keep alive what she called “the learning of the imagination.” It is still active today, running lectures and courses devoted to this learning.

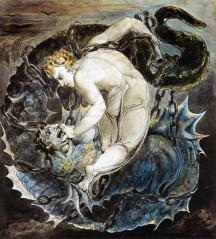

“Temenos” is a Greek word meaning the “sacred space” or “gathering” before the temple, and it is an apt name for Raine’s academy. Raine, who is perhaps best known as a scholar of William Blake and other English Romantic poets, discovered that there was a whole tradition in the west of what we can call “imaginative knowledge,” that was lost to us. This was a knowledge that was as “real” and “true” as the kind of knowledge we are more familiar with – scientific knowledge or practical knowledge – but that concerned itself with aspects of reality that our more commonplace knowledge ignored or was unaware of or, in many cases, actively rejected.

What is this other kind of knowledge and why was it rejected? In a broad, general sense we can say that where the kind of knowledge we are more familiar with deals with the outer, external world - how to manoeuver through it and control it, the kind of knowledge that is absolutely necessary for life - this other, imaginative knowledge is concerned with our inner world, with what we used to call the soul but which we now speak of as consciousness. It is concerned with our inner experience, with states of being, with values, meanings, insights, intuitions and the other mysterious phenomena that make up our interior landscape and help make us human.

This kind of knowledge was rejected because it is precisely these kinds of intangible things that the kind of knowledge we are more familiar with cannot deal with adequately. It can tell us what is wrong with our car engine or how to get to the moon, but if we want to know the meaning of life or why a sunset is beautiful, it is irrelevant, absolutely useless. No amount of scientific analysis of a sunset will reveal to us the mystery of its beauty, just as no amount of pragmatic advice about how to “get on” in life will tell us its meaning. For this kind of knowledge, “meaning” and “beauty” are only subjective, they exist only “inside our heads”. My car engine and the moon are outside; they are objective, “real.” What I know about them is real knowledge and true for everyone. What I find meaningful and beautiful is true only for me. According to our common ideas, that is not knowledge. At best, it’s opinion, and only as good as any other.

Although living and influential in the past, this imaginative tradition, Raine saw, had been lost or, more accurately, pushed aside and relegated to the gutter, with the rise of the modern age and the development of what we know of as science and the measurable, quantifiable knowledge associated with it. At this time, around the early seventeenth century, for something to qualify as knowledge it had to be amenable to being measured and quantified. The sort of interior experience the tradition of imaginative knowledge was concerned with could not meet this requirement. It was concerned with quality, not quantity; with meaning, not measure. The sorts of things it engaged with could not be encompassed with a slide rule or measuring tape . They could not be touched or felt or weighed or in any way perceived by the senses. Because of this they soon found themselves being regarded as non-existent, or at best understood as negligible by-products of the actual measurable – that is physical – processes that the new quantifiable knowledge believed accounted for them.

This belief in the unreality or insignificance of our inner experience – from the quantitative perspective – remains today. It is very easy to find evidence for it. The whole push to “explain consciousness” in physical terms – as a product of neurons and electro-chemical exchanges in the brain – that has been going on for some time now, is an example. But because the new, quantitative way of knowing was so impressive and successful and seemed to put an enormous power into man’s hands, it went ahead with confidence, and either ignored the warnings about the consequences of the loss of our inner world or rejected them as nonsense.

The tradition of imaginative knowledge lost a great deal of its prestige at this time. Up until then it was not considered, as it is today, mere nonsense and superstition, but a legitimate concern of scholars and philosophers, and its fall from grace was considerable. But, as Raine saw, it did not disappear. It merely went underground, and became a kind of subterranean stream, surfacing from time to time, and informing sages and poets like Swedenborg and Blake, but also Goethe, Novalis and the German Romantics, and many other artists and poets and musicians and philosophers. By the late nineteenth century it flowered forth as the modern “occult revival,” responsible for Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. By the early twentieth century we have Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy, the work of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, and even psychologists such as Carl Jung drawing on elements and ideas bubbling in the underground stream of our lost tradition.

In my books The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus and The Secret Teachers of the Western World, I write about the history of this “lost tradition,” which has been lost only for the past four centuries. “Misplaced” or “hidden” may be better ways to characterize it, as something being “lost” implies that it has gone missing accidentally, and the disappearance of this tradition of imaginative knowledge had nothing accidental about it. It was deliberately relegated to the rubbish bin of ideas, and as I show in Secret Teachers, was subject to a kind of “character assassination.”

In these books and others, I show this tradition’s roots in the ancient philosophies and beliefs of antiquity and how, with the rise of quantifiable knowledge as the only accepted form of knowledge, it fell from a position of considerable prestige into ignominious disrepute. When we recognize that figures such as Copernicus and Isaac Newton, architects of the modern age, and other A-list western intellectual stars, such as Dante and Plato, subscribed to much of the lost tradition, we can see that it is something of value and significance and that to lose such a learning is indeed a loss.

Raine herself saw the Neoplatonic tradition, with its vision of the One, the varied forms of the Anima Mundi, or Soul of the World, and the struggle of the individual soul to free itself from material bondage – its exile in the world - and return to its source, as the guiding idea behind the symbols and metaphors that inform the Romantic lyrical tradition. What this poetry was about fundamentally was the soul, and its journey here, in an often dark world. Ultimately this vision went back to Plato. But she knew that Neoplatonism was not the sole source of the knowledge of the imagination she discovered in Coleridge, Yeats and other poets. It was one of many sources rooted in the past, such as Hermeticism, Kabbalah, Gnosticism, and also the wisdom of the East, that fed the subterranean stream of the lost tradition. The tradition of the imagination has appeared in many forms, each related to the others, but each also unique. But each also fed and drank at the same source.

All of these traditions offered a different way of knowing the world and a different way of understanding our place in it, than that of the quantifiable, measurable view. In a general sense we can say that they spoke of a world that was living, conscious, interconnected, and receptive to human entreaty. Human beings themselves were a part of this world and shared in its spiritual, vital character. We could communicate with it. We participated in it. We could speak with the spirits of nature and commune with the gods. It was a world that we can only dimly envision now, through our imagination – or remember it from our childhood - but it was a world in which imagination was the fundamental medium linking all together.

But with the rise of the new quantitative way of knowing, all this changed. The gods and spirits were evicted from the world. In order to understand the laws of planetary motion, we had to reject the idea, expressed eloquently by Dante, that it was the angels, or love, that moved the stars. Yet, Johannes Kepler, who discovered the laws of planetary motion which we use today to send our probes out into the further reaches of space, was himself a passionate devotee of our lost tradition.

If someone responsible for the knowledge that allows us to send interstellar probes out beyond our solar system and into the infinity of space was a student of our lost tradition, it behooves us, I believe, to try to understand why this should be so. It is also a reminder that in trying to revive or restore or renew this lost tradition, the aim is not for it to replace the kind of knowing we associate with science and the practical business of life, but to complement it. Both are absolutely necessary and it is only by embracing both that we are fully and truly human.

The true source of this tradition of imaginative knowledge, however, is the imagination itself. All gods exist and have their origin in the human soul, William Blake tells us. He goes even further. The entire world we perceive with our senses is a product of imagination – not in the sense of it being “fake” or “unreal” but in the sense that our inner world, our mind, for sake of a better word, has precedent over the outer one and is indeed responsible for it. As the essayist and philosopher of language Owen Barfield – a friend of C. S. Lewis and a brilliant expositor of the ideas of Rudolf Steiner – said, “Interior is anterior,” meaning that our inner worlds come first, before the outer world. This, of course, is the exact opposite of what modern science tells us today. For it, the outer, exterior, physical, material measureable world comes first and is, in some way they can’t explain just yet – but they are working on it – responsible for our inner ones.

I don’t accept this and I don’t believe the people in this room accept it. But that is the situation today. And it is because that is the situation today that we have what this conference is concerned with: a crisis of the ego. What I hope to do in this talk is to show that by regaining this lost knowledge of the imagination, by becoming aware of and participating in this tradition of the imagination, we may be able to overcome this crisis. With a grasp of what this knowledge of the imagination truly means, we can pass through this difficult time, this “time of troubles,” as the historian Arnold Toynbee spoke of the crises that challenge civilization, and begin to work on the real challenge, that of taking the next step in the evolution of consciousness.

For that is what I consider our current crises to be. The environmental, social, political, economic and other planetary challenges facing us are the hurdles we have to leap, the barriers we have to surmount, in order to make the shift into the next stage in human consciousness. Or, rather, it is by making that shift that we will be able to face these challenges successfully. The two are intertwined. Toynbee saw “challenge and response” as the motor of history. If a challenge facing a civilization is too great, it fails and goes down. If it is too easy, the civilization becomes complacent and decays. But if the challenge is “just right”, then the civilization finds the will and creativity to meet it, and continues to grow. I call this the “Goldilocks theory of history,” and it is something, I think, that we can apply to human consciousness itself. If you know the English fairy tale of Goldilocks and the three bears, you will know that out of three choices, she always finds what is “just right.”

There are no guarantees and it is up to us to pull it off. But if we don’t, I see little hope of a bright future. I don’t mean to be gloomy here, just realistic. The environmental challenges facing us are enough to suggest this, and the political ones are no help either.

But how can a tradition of imagination, however important, help deal with the kind of real, solid, hard, physical crises involving climate, wealth, social justice and so on that face us today? To answer that I will need to take a look at what I mean when I speak of imagination.

When we think of imagination we usually see it as some kind of “substitute” for reality. We think of fantasy, day-dreams, wish-fulfilment musings offering unsubstantial realizations of a life much more interesting, fascinating, exciting – in general in all ways much better than our own. We think of imagination as “make believe,” as pretence, and sigh wistfully about “having our dreams come true,” and are usually woken up with a start and the admonition that we have let our imagination “run away with us.” We drift into a fantasy of some more satisfying way of life, then sigh and admit that it was “just our imagination.”

Or we think of imagination as a tool for being innovative, for coming up with novelties that will keep us at “the cutting edge” of our profession. It helps to bring us the latest in technology, and keeps it “state of the art” and “fresh from the drawing board.” Imagination in this sense can be applied to anything, from computers to lipstick, from automobiles to swim suits. It is responsible for fashion – or perhaps we should say that a lack of imagination is responsible for that.

Of course we also give imagination an important, essential place in the arts. This is where it is most respected. Great literature, great painting, great music are all dependent upon the powers of the imagination, as are the lower ranks in these pursuits. This is perhaps the one realm in which the quantitative way of knowing will allow its qualitative way some freedom, although of course we know that many serious people see the products of imagination in this way as little more than ways of “escaping reality.” We say that people who spend too much time reading fiction or watching films are guilty of escapism, of running away from life - although much of the fiction and the films made today seem themselves something to run away from.

But ultimately, when it gets down to business, however powerful and moving a novel, painting, symphony, or even a film may be, in the end it, like the other substitutes for reality, is “unreal.” They are fiction, even if the novel, such as War and Peace, is about “real” events, or the painting depicts an historic scene. And if it is, like music, a non-representational art, then it is in the end really nothing more than nice sounds, vibrations of air that, for some odd reason, give us a sense of joy or comfort or what have you.

The point here is that no matter how powerful or meaningful we find a work of art, in the end, for the quantitative way of knowing, that power or meaning is less real than the paper, ink, canvas, paint or vibrations of air that convey it. Paper, canvas, ink and vibrations can be measured; meaning can’t.

This prejudice toward the unreality of the imagination is a difficult thing to excise. It is emphasized in the very definition of the word, at least in English. The Oxford Dictionary calls it a “mental faculty of forming images of objects not existent.” The Cambridge Dictionary calls it “the ability to form pictures in the mind that you think exist or are true but are in fact not real or true.” Merriam-Webster calls it “the ability to imagine things that are not real.”

We get the point. There are two things I want to say about this. The first is that although “imagining” in the sense of making a mental picture of something is, of course, a great part of “imagination,” it is not the only thing that is important about it or the only “power” possessed by imagination. The way I see imagination, it is not a faculty or a power in a specific sense, in the way that, say, our eyes have the “power” of sight or our ears the “power” of hearing. It is the means by which we have any experience at all. You can have 20/20 vision and hearing like sonar, but if you lack imagination you will be blind as a bat and deaf as a log. Imagination is something so fundamental that we cannot point to one limited expression of it and say, “That’s it. That’s imagination.” It is a kind of “intuitive glue” that holds all of our experience together; without it, everything would break apart into disconnected fragments. We can’t imagine what it would be like to be without imagination, because we would need imagination in order to do so.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead spoke of the fundamental elements of our experience as things “incapable of analysis in terms of factors more far-reaching than themselves.” These are things so basic that we can’t get under or away from them. We can’t analyse anything without already taking them for granted. Imagination, I think, is one of those things. It is so much a part of memory, self-consciousness, thought, perception, and the rest of our inner experience that it is almost impossible to pry it apart from them or any of them from each other. We can talk about these elements of our inner world as separate phenomena but we soon find that they blend into each other and that to demand an unyielding, fixed definition of “imagination” or any of these other imponderables would actually make them more obscure. We recognize what they mean tacitly, implicitly, and to throw the spotlight of analysis on them too harshly causes them to fade from our grasp. They have their own character, their own shading, contour and shape, but they run in parallel with each other.

The other thing I would say regarding a definition of imagination is that the one I do find most profitable to follow comes from Colin Wilson, a British writer and philosopher whose work has been an enormous influence on my own. He saw imagination as “the ability to grasp realities that are not immediately present.” Not, as our official definitions have it, as a means of creating “mental images” of non-existent things. But a means of grasping reality itself. I would only add to Wilson’s definition the fact that we often need imagination to truly grasp the reality that is right in front of us, staring us in the face.

Wilson knew this, and it is this kind of passivity before the outer world that our consciousness often exhibits – what he calls “robotic consciousness” - that he spent a lifetime analysing in order to overcome. But what he meant by “realities that are not immediately present,” is that we are often hypnotized into accepting whatever “reality” may be in front of us at the moment as the whole of reality, or at least of the reality available to us at the time. We are, he says, “stuck” in the present, hemmed in by our immediate experience in the same way that we would be hemmed in by four walls if we were locked in a room. Plato, in fact, knew this ages ago, when he compared human beings to prisoners chained and forced to live in a cave, and who take the shadows they are compelled to see for “reality.”

Plato believed the pursuit of philosophy was a way of exiting the cave. He is right. It is, and the Neoplatonists whose vision informed Kathleen Raine’s Romantic poets knew it. But sometimes we can find ourselves outside the cave and in the bright daylight spontaneously. It is in such a moment that imagination in the sense of “making real” “realities that are not immediately present,” comes into play. And even here, the notion that imagination, instead of “make believe” – which is how we usually understand it – is really about “making real,” is expressed quite clearly. Anytime you “realize” something – that is, make it real to you – you use your imagination to do so. That is what “realizing” something means: making it real.

Let me give you an example of such a moment that Wilson refers to in his books and which seems rather appropriate for the setting of this conference. It comes from the novelist Hermann Hesse, from his novel Steppenwolf, and here we are in Hesse’s hometown. I’m sure you know the story. Harry Haller – who we must assume is in at least some ways Hesse himself – is a middle-aged intellectual who really has nothing to complain about. He has enough money to live on, the freedom to do what he wants, and no responsibilities of any kind. Yet, he spends his days avoiding suicide. Why? Why should his freedom, which is something he has always wanted and has struggled and sacrificed to attain, have become a burden? It makes no sense. Yet it has and in the beginning of the book we find him wandering around an unidentified city – most likely a blend of Basel and Zurich – avoiding the razor blade.

At one point he sits at a café and orders a glass of wine. Then, as he sips his good Elsasser, something happens. His despair lifts and suddenly he is transformed. “A refreshing laughter” rises in him, and from out of nowhere, he is flooded with memories: of paintings he has seen, places he has been, of experiences he has had but of which only he knows. “A thousand pictures” were stored in his brain, and now they have come back to him, not as dim, faint recollections, but as living, vital realities. These things have been and still are real, and the recognition of their reality, the realization of it, has now completely changed the wretched Steppenwolf’s mood. He is not trapped in the prison of the present moment, and the dullness he feels toward life is a colossal mistake, his ideas of suicide an absurdity. As he becomes aware of more reality, he becomes more real himself. “The golden trail was blazed and I was reminded of the eternal, and of Mozart and the stars.” Would that we all were!

Harry Haller was reminded of the reality of the stars, of Mozart and of the eternal. But did he actually forget that Mozart existed, or that the stars did? (We can put the eternal aside for a moment.) Did he forget about their existence in the same way that he might have forgotten his keys or a friend’s telephone number? What exactly is he “remembering” here?

What Hesse means by being “reminded” here is not the same as when we are reminded of some fact we have forgotten, say, the year of Mozart’s birth or when he composed the Jupiter Symphony. What has set the golden trail ablaze is not some fact like this coming to the Steppenwolf’s attention. He does not say “Oh yes. How could I forget? Mozart existed and wrote all that music. And the stars and the eternal exist too. How silly of me.” He was in full possession of these facts before he drank his glass of wine. But he was not in full possession of the reality of those facts until he did. Something prevented him from remembering it or somehow came between the acknowledgement of the fact and the appreciation of its meaning. And now the wine has somehow removed this impediment and the reality of things – or at least that part of it he has “forgotten” – comes rushing in. No surprise that wine and poetry have long been fellow travellers.

And it is because the Steppenwolf is not in full possession of reality that he finds the “lukewarm and insipid air of his so-called good and tolerable days” absolutely unbearable and he spends his evenings wondering whether or not he should slit his throat.

What has saved him from doing so that particular evening is precisely the reality of other times and places, coming back to him and rescuing him from the misconception that reality is whatever happens to be in front our noses at the moment. It is not. These things that come rushing to him really happened and they are really a part of his life. They happened in the past, yes, but what of it? What is time that it should decide whether something is real or not? It is all well and good to “be here now,” as much sage wisdom advises. But it all depends on how big is “here” and how long is “now”. “Here” can mean the entire universe and “now” all eternity – if, as the teachers of the imagination tell us, we know how to enter them. At that moment when the wine released the restraints on his imagination, the past was as fully real to the Steppenwolf as the present was. Even more real, as the present he had taken for reality was a confidence trick that, luckily, he has seen through.

So that is an example of how imagination, rather than dealing in unrealities, is an absolutely necessary ingredient in our capacity to fully grasp actual, well-established realities. And again, this is not some metaphor or “manner of speaking.” Harry Haller may be a fictional character, but anyone who knows about Hesse’s life knows that an H.H. turns up in more than one novel and is usually not very far removed from Hesse himself. I think we can take it as given that the kind of experience Harry Haller had was also had in some way by Hesse himself. He certainly entertained suicidal thoughts on more than one occasion. It was precisely in order to understand the meaning of such experiences, that Hesse wrote Steppenwolf and his other novels.

In general Hesse’s heroes find something “missing” in life and head out on the road in order to find it. And on the way they have strange moments when what is missing is suddenly found. And like Harry Haller they do feel “How could I forget?,” but not about this or that fact, but about the reality of their experience. Indeed, how could they forget that? What is missing? Reality, or our grasp of it. How can we regain it? Imagination.

This is not a talk about Hesse, so I should move on. But you can find other examples of the “Mozart and the stars” experience in Steppenwolf and in Hesse’s other novels. Now let me offer a few examples of other types of experience associated with the “learning of the imagination.” Let me give you one from a younger contemporary and countryman of Hesse, although one who had very different views on life and society.

In his unclassifiable work The Adventurous Heart, the writer Ernst Jünger has a section entitled “The Master Key.” In it he offers an example of a kind of imaginative knowing that is direct, immediate, much in the way that the reality of the past came to Hesse’s Steppenwolf directly. “Our understanding is such,” Jünger writes, “that it is able to engage from the circumference as well as at the midpoint.” “For the first case we possess ant-like industriousness, for the second the gift of intuition.” Jünger comments that “for the mind that comprehends the midpoint, knowledge of the circumference becomes secondary – just as individual room keys lose importance for someone with the master key to the house.”

Knowing from the mid-point, or, we could say, at the bull’s eye, is a way of knowing that is direct, not discursive. It does not follow steps or stages but goes straight to the center, to the heart we might say. It possesses a miraculous accuracy but it has one drawback. It is unable to explain how it knows what it knows, how it came to its knowledge. Intuitions come to us, suddenly, out of the blue, and we just know they are right, even though we can’t explain why or how. That is the benefit of the ant-like industriousness of those who proceed from the circumference – that is, using our usual way of knowing, with all the individual keys to all the separate rooms. It is dull and repetitious, but once we know something in this way, we can tell someone else how we know it, and show them so that they can know it too. I can’t share my intuitive bull’s eyes in the same way, although if I am an artist or creative in some way, I may be able to create something that can spark an intuition in you. But I can’t write out a formula for one in the same way that I can, say, for a chemical experiment.

This kind of direct knowledge appears in different ways. Goethe experienced something of it when he perceived his Urpflanze in the Botanical Gardens in Palermo during his famous Italian Journey. Gazing at the plants there in the hot Mediterranean sun, Goethe believed he could see what he called the “Primal Plant,” the archetypal plant from which all others emerge and with which all others are still in sympathy, that is, connected. It was “real” but it was not physical, and to see it require a long training and discipline in the imagination which, for Goethe, was as precise an instrument as any used by his fellow scientists. Goethe wrote about his experience of “seeing ideas” – as his friend Schiller called it – but he knew that it was “impossible to understand just from reading.” One had to see the Primal Plant for oneself, and that meant training the imagination to do so.

The kind of inner seeing that Goethe practiced in order to see his Urpflanze has much in common with what the alchemist and Egyptologist René Schwaller de Lubicz called “the intelligence of the heart.” This was a way of understanding the world that de Lubicz believed was at the center of ancient Egyptian religion and civilization. It too was a way of seeing into things, of looking into their interior and grasping the interconnectedness of all experience. De Lubicz speaks of a way of knowing the world in which we can “tumble from the rock that falls from the mountain,” “rejoice with the rosebud about to open,” and “expand in space with the ripening fruit.” As with Jünger’s “master key,” “the intelligence of the heart” is a way of going directly to the center of experience, of participating with it, in a way that our usual way of knowing, from the outside, finds incomprehensible. It is a way of knowing that, using a term from the esoteric tradition, we can call a gnosis.

There are other forms of imaginative knowing, such as the inner journeying of seers such as the 11th century Persian mystical philosopher Suhrawardi, the Swedish scientist and religious philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg, the psychologist Carl Jung, and the 20th century Iranologist Henry Corbin. I explore them in my book Lost Knowledge of the Imagination and unfortunately I can only mention them here. In this talk I have focused on one aspect of our imaginative knowing, that of its power to grasp reality. But as I say, reality extends into more directions than we might immediately recognize. What Suhrawardi, Swedenborg, Jung, Corbin, and many others discovered was that our imagination is our entry point into the little explored universe each of us carries around inside our heads. A world extends outside of us infinitely. There is also an inner world that extends into an equal infinity within our minds, with its own landscapes, geography, laws, and, most strange, inhabitants. But that I will have to leave for another talk.

What I want to do now, as I see I have to bring this talk to a close, is to show why I think recognizing that imagination as a means of grasping reality is something of vital importance to us, and why it is necessary in order to meet the challenges facing us in our crisis of the ego. The importance of having a good grasp on reality should not require too much argument, to be sure. What is necessary is to show that although we think we already have reality well in hand, we don’t. And again, what I mean by “reality” here isn’t anything abstract or metaphysical or spiritual or cosmic. I mean common, everyday reality, the unavoidable kind. It was his weak grasp on this reality, the reality of his life, that led Hesse’s Steppenwolf to grow to hate his pleasant, comfortable existence and consider slitting his throat as a stimulating alternative. We can say this is our existential reality.

If a man as intelligent, cultured, and mature as Hesse’s Steppenwolf – and, we can assume, Hesse himself – could so lose his grip on what was real and meaningful about his existence – “Mozart and the stars” – that he could be brought to thoughts of suicide, how better would a less developed individual fare when subject to the same tendency we all have to what Colin Wilson calls “life-devaulation,” which is really a way of expressing our common sin of getting used to things and taking them for granted? What does “getting used to” or “taking for granted” mean? It means that we begin to notice only the fact of some reality or other, and lose sight of its meaning. It means a failure of our imagination to hold on to the full reality. We devalue it. The mere fact is easy to retain – our senses help us here. To retain the meaning requires a kind of effort on our part, and we easily forget this or find it too taxing to make. And because we fail to make this effort, we fall into the trap of accepting the half-reality we perceive – the side of it available to our senses – as the whole of reality, and we base our decisions about life on this diminished picture.

Because of this we are apt to make bad decisions, ones based on only what is immediately before our eyes. That is, short-sighted ones.

This cannot be good.

We can say that all acts of imagination are designed to in some way retard or reverse this process. Going about life in this state is only a kind of half-living. We are all subject to this. We are all Steppenwolves, of one kind or another. But we too can all remember Mozart and the stars. And it is important that we do because the crises facing us will require our grip on reality to be as firm and tenacious as we can make it. In fact, it’s the case today that in many ways “reality” is up for grabs. This is something I have written about in my most recent book, Dark Star Rising: Magick and Power in the Age of Trump, which looks at how certain ideas about how we “create our own reality,” stemming from occultism and postmodernism, have informed contemporary politics in the United States, Russia, and also in Europe. So the question of securing a firm grip on reality is not solely a philosophical or psychological one. It has also bled over into politics. I would say that in general today, reality is under threat.

Regaining the lost knowledge of the imagination, or even recognizing that such a knowledge is there to be regained, can, I believe, help us here. It may be a means by which we can find a way through our crises that brings the two dimensions of our experience – facts and their meaning - together in a collaboration that is “just right.” If so, that would be a reality worth creating.