My new book, Dreaming Ahead of Time, about my experiences with precognitive dreams, synchronicity and coincidence, will be published by Floris Books this January. In it I look at some of the dreams I have been recording over the last forty years, in which bits and pieces of the future have turned up. How does this happen? Beats me, but I am as convinced that it does as I am about anything else. In the book I look at some of the ideas about precognitive dreams of earlier explorers, J. W. Dunne, J. B. Priestley, T. C. Lethbridge, and also at Ouspensky’s ideas of a “three dimensional time,” Jung’s synchronicity, some very remarkable coincidences, and Colin Wilson’s notion of Faculty X, which allows us to travel to “other times and places.” I have a premonition you will enjoy it

Here are some thoughts about sex that I’ve had to cut from a book I am working on. They seemed too interesting to leave in my files.

Sex and Imagination

By

Gary Lachman

In a book I’ve been working on recently, sex has turned up quite a bit. Here I’d like to spell out in some detail ideas and intuitions about it that, at least where the male of the species is considered, strike me as being of fundamental importance. This should not be surprising. Nietzsche once remarked that “The degree and kind of a man’s sexuality reaches up into the topmost summit of his spirit.” What I hope to briefly explain here is exactly how that can be the case.

My analysis is based on the “phenomenology of the sexual impulse” carried out by the existential philosopher and novelist Colin Wilson. For readers not familiar with the term, phenomenology simply means a close observation and descriptive account of experience, of, that is, phenomena, whether they appear to our senses or to our mind. The tree that we see in the garden is a phenomenon; so is the one we see in our mind. Phenomenology is interested in how each of them “appear” to consciousness. There is, of course, a whole philosophical school based on the work of Edmund Husserl, the founding father of phenomenology, with much lively debate about its aims and premises, but that needn’t concern us here. Fundamentally phenomenology is about observing and understanding our inner states. Put in the simplest terms, it is about paying attention to what is going on in your head. It is essentially a method of grasping the “structures” or processes making up our conscious experience, of becoming aware of the interior gestures, we could say, that allow for that experience to take place.

An example would be biting into an apple and enjoying the taste: that’s the experience. A phenomenological analysis of the experience would seek to grasp how it is that you enjoy it, what mental “acts” are involved in the enjoyment. The enjoyment is not in the apple, or at least not solely in it, because there are times when, for whatever reason, we don’t enjoy apples. So where is it? Listening to music is another example. We are carried away by Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony. Then we decide to listen again and try to grasp how Mozart achieves his effect with such surety and simplicity, and not in musical terms, but in those of our own inner structure. This may spoil our enjoyment – it often doesn’t bear thinking about, hence the unpopularity of that pursuit - but we can come to understand it, and what mental acts we perform that enable us to enjoy it, acts of which we are usually unaware, that is, of which we are unconscious.

It may seem that our enjoyment of the music requires no acts at all: it simply happens. Husserl says no. At a level below your enjoyment, making it possible, your consciousness is reaching out to meet the music, as it were. If we are distracted, or bored, or something else “takes our mind away,” as we say, we no longer hear the music, although the CD may still be playing. The soundwaves may be hitting our ears, but the signal isn’t getting through. Our attention is elsewhere. The opposite experience happens when a piece of music we have heard countless times and that we think we know very well indeed suddenly sounds new and fresh, and we are surprised at the enjoyment we are receiving from it. How does this happen?

Husserl’s answer, and the basic premise of phenomenology, founded on empirical observation, is that our perception, our consciousness is intentional, although we are not immediately aware of this.[1] To put it simply, our consciousness does not merely reflect a world that is “already there,” as a mirror reflects what happens to be in front of it. Consciousness reaches out and “grabs” the world, as our hands do the apple we have just bitten, and indeed, as our teeth do the apple as we bite it. It “intends” it. Its relationship to the world, to experience, isn’t passive, but active. I could extend this metaphor and say that we “digest” experience just as much as we do the apple. And just as we can have a weak or strong “grasp” on our experience, we can digest it well or badly too.

I say “consciousness intends,” but what I really mean is that we do, my consciousness and your consciousness, but at a level below our surface awareness. That is why I think that when I bite into an apple and enjoy it, it “just happens.” It doesn’t. As Wilson writes, “there is a will to perceive as well as perceptions.” Most of the time we are unaware of this will; our acts of intentionality occur below our conscious awareness. We are usually only aware of our perceptions, not the will behind them. But there is one intentional act that we can become aware of, and it occurs in a heightened state of consciousness, one more intense than our usual passive state. This is the sexual impulse.

In a series of books written over several decades, Wilson developed what we can call a kind of “sexistentialism,” a phenomenological investigation of exactly what is behind the sexual impulse; what, that is, it “intends,” its aim.[2] Exactly what that aim is, was the question Wilson posed himself. Or, as he put it, he wanted to “be able to express the meaning-content of the sexual orgasm in words.”

When it comes to the orgasm, most men are satisfied with groans; and to them the answer to the question of what the sexual impulse aims at would be glaringly obvious, as obvious as a hungry man’s aim in having a meal before him. Wilson wanted to articulate the intentional structure of the sexual orgasm, and in doing so, he soon saw that the relation of the male sexual impulse to its object is almost nothing like that of a hungry man to a steak. What makes for a satisfactory sexual experience is far more subtle than what makes for a satisfying meal, although both can be enhanced with a bit of spice. Wilson’s conclusion was that, far from being driven by an insatiable libido, as Freud would have it, sex in human beings – male and female – has more to do with achieving states of intensified consciousness than with satisfying any animal appetite. That is, it has to do with our evolutionary drive, our inherent urge to grow. And that intensified consciousness, that growth, is rooted in the imagination. Wilson anchors this point in the very observable fact that if we are hungry, an imaginary meal will not satisfy our appetite, nor will an imaginary drink satisfy our thirst. But an imaginary sex partner can satisfy our “sexual appetite” as much as – and often better than – a “real” partner can. This is why more than one writer on sex has remarked that masturbation can be a more gratifying means of sexual satisfaction than “real” sex.

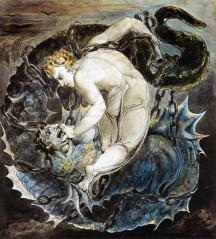

For most of us, sex is the closest we get to anything like a mystical experience - if, of course, we are lucky: it is not absolutely reliable and there are no guarantees. But when it does work – and what we are looking at here is precisely why it does, when it does - it is an experience of tremendous power, beyond anything we experience in everyday life, what Nietzsche called “the Dionysian,” referring to the ancient Greek god of drunkenness, ecstasy, and abandon. Some of us are so impressed with this power that we spend our lives seeking it out, or at least seeking out the experience that enabled us to feel it. We call these men Don Juans or Casanovas. There are female equivalents, although the urge behind nymphomania is not the same as that behind the seduction addict. And of course, there is a whole body of literature relating to the spiritual and mystical aspects of sex, from Tantra to various other kinds of spiritualised sexuality. As Wilson writes, “The ‘origin of the sexual impulse’ is not the ‘libido’, “it is an intentionality that is not confined to sex alone, but that also projects the ‘meaning’ of man’s aesthetic and religious activities.”[3] This is why Wilson argues that the same “intentional act” that transforms a two dimensional image in a magazine into an object of intense sexual excitement – i.e. a centrefold – so that it can elicit the same physiological response as the “real thing,” is the same intentional act that allows us to enjoy Van Gogh’s Starry Night or to see the flower in the garden as beautiful.

Like sex, art and religion are other means of intensifying consciousness. What all three have in common is that they can temporarily lift us out of our everyday, ordinary consciousness, and make us aware of wider horizons of meaning and of deeper areas of our being, that are ordinarily obscured. Religion and art have always been associated with man’s higher nature, his values and ideals, with, we can say, his evolution into something more than an animal. Sex has rarely, if ever, shared this status, at least in the west.[4] In fact, it has more often been vilified as a regrettable remnant of our animal past, although in fact, human sexuality is as unlike that of animals as it could get; we do them and ourselves a disservice when we speak of “beastly lusts.”

Why?

Because as mentioned, sex in human beings has more to do with the imagination, with what is going on in the mind than in what is taking place in the genitals. Many of us are all too familiar with the fact that it is invariably the case that if the mind isn’t involved – if we aren’t “into it” – then it is easy for the genitals not to be too. As far as we can tell, there is little going on in the minds of animals as they mate; often enough the operation is over too quickly for them to have had any thoughts about it, were they were capable of having them. This is why the Russian religious existentialist philosopher Nicolai Berdyaev could say that “It is quite possible to say that man is a sexual being, but we cannot say that man is a food-digesting being.”[5]

Clearly, sex has to do with organs – penises and vaginas – in the same way that digestion does, but it isn’t limited to them as digestion is limited to our stomachs; it reaches beyond them to permeate our entire life. I love food as much as the next man – indeed, Bernard Shaw said there was no greater love -but I am unaware of any great works of art based on digestion; there is, I believe, no Romeo and Juliet, no Carmen or Tristan and Isolde inspired by an appetizing dinner. And we rarely have to be “into it,” in order to enjoy our meal; we simply have to have an appetite. Indeed we often read, watch television, or carry on a conversation while eating, in a way that we couldn’t while engaged in sex. And if our sex partner were so involved in some additional activity as these, it would, more than likely, put us off. With sex, there is a need to focus our consciousness in order to get its full benefits in the same way that an artist needs to focus his consciousness on his work and that we need to focus ours on his finished product when we stand before it in a gallery.

Because of this, Wilson argues that it is a mistake to see sex as a “low” or “base” drive, as Freud did, or as an annoying but unavoidable necessity for perpetuating the species, as the church does. The truth is that the drive behind sex is exactly the same as that behind the highest forms of human creativity. That is, it is a drive for greater consciousness.

How did Wilson arrive at this conclusion? From a study of sexual perversions – or I should say from becoming aware of the difficulty in determining what sexual behaviour counted as a perversion. This was – is- difficult because we don’t have a clear idea of exactly what constitutes “non-perverted sex.” Which is another way of saying that we don’t have a clear idea of what “normal sex” is, although we may think we do. For nature’s purposes, sex means offspring; that is, its aim is procreation, and for the most part, animals do not engage in many perversions about it. Clearly, humans mate in order to have children, but they do not mate only for that reason, and I think it is safe to say that most of the sex we engage in isn’t concerned with that at all; indeed we go out of our way to ensure that no progeny will result from our revels.[6] The Russian philosopher Vladimir Soloviev wrote a book, The Meaning of Love (1892), that rejected the utilitarian or Darwinian views of sex as a means of improving the race through selective breeding, and argued instead for its transformative power for the individuals concerned. Wilson agrees. The question he asked himself was “What part does sex play in man’s total being?,” to which we’ve seen replies from Nietzsche and Berdyaev.[7] But this only raises the question of what we mean by “man’s total being?” Wilson concluded that “the problems of sex and the problem of teleology (man’s ultimate purpose) are bound together, and neither can be understood in isolation.”[8]

But if offspring – bigger and better ones – aren’t the aim, or at least not the central one, of the sexual impulse, then what is? Wilson argues that the notion of “sexual fulfilment” is linked to what we perceive as the limits of “human nature,” limits that the sexual orgasm undeniably exceeds – hence its popularity. Its power suggests “an intuition of some deeper, more ‘god-like’ state of satisfaction for the individual.”[9] If this is the case then, as Wilson writes, “A satisfactory notion of ‘ultimate sexual satisfaction must be bound up with some larger mystical vision about the purpose of human existence.”[10]

The notion of some “ultimate sexual satisfaction” leads us into the realm of perversion because it is in quest of such satisfaction that perversions arise. If one was satisfied with the usual roll in the hay, they would not appeal. What do sexual perversions actually do? They act as a spice, making the ordinary, normal act more interesting, just as cayenne pepper puts a kick into your casserole. We know how a spice works on food. How does it work with sex? What exactly is the spice that is added?

For Wilson, it is “the forbidden.” “The major component of the sexual urge is the sense of sin – or, to express this more moderately, the sense of invading another’s privacy, of escaping one’s own separateness.” “The idea of the forbidden is essential in sex; without the sense of the violation of an alien being, sexual excitement would be weakened, or perhaps completely dissipated.” “Sex can never, on any level, be ‘healthy’ or ‘normal’. It always depends on the violation of taboos – or, as Baudelaire would have said, on the sense of sin.”[11] And as Wilson points out, “the forbidden” is an idea and needs to be grasped by the mind, by, that is, the imagination. You need to know you are breaking the rules in order to get the kick out of breaking them.

Yet, in our time, this requires a certain amount of self-deception. Why is it that now, in the twenty-first century, when we all know sex is just a normal part of life and that there is really nothing “wicked” about it, we nevertheless still talk of being “naughty” and having a “dirty weekend,” and of acting out some of our kinky “secret desires?” Escort services cater to this frisson of “transgression,” offering a variety of fantasies in which the client can indulge in a spectrum of “forbidden” activities from fairly standard perversions like sodomy and oral sex, which are by now more or less mainstream, to sadism, masochism, and more acquired tastes such as urophagia (drinking urine) and coprophagia (eating faeces), to any number of role-playing sex games involving nuns, schoolgirls, even aliens. The fetishism that drives these forbidden acts is itself proof that the main element in sexual satisfaction is the imagination, for what else bestows the seemingly magical power of evoking considerable sexual excitement on ordinarily non-sexual items such as a raincoat, an umbrella, or an apron, to name just a few? And I should point out that the same intentional act that animates these otherwise ordinary items and transforms them into objects of sexual excitement is the same intentional act that makes you “into” the sex you are having with your partner. In this sense, even a real partner is a fetish – and those who understand this remark have understood the point I am trying to make.

Yet, as Wilson points out, these spices soon lose their savour, or rather, we soon grow used to them and require something a little more spicy to get the same kick. Readers of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom are soon weary of the spices he provides, heaping them up on each page, and which fairly soon have very little to do with sex and more to do with providing any kind of shock possible. And what exactly is the kick? It is a sudden vivid awareness of the reality we have let slip from our mental grasp, which in this context is the sexual act. (And it is the same reality that we catch glimpses of in aesthetic, mystical, and ‘peak’ experiences.) That is, it is increased, intensified consciousness. This is why some couples install mirrors in their bedroom, so that they can see themselves in the act. (These days perhaps they take selfies…) The spices – or perversions – serve as “alarm clocks,” to take a metaphor from Gurdjieff, that “wake us up,” reviving our flagging consciousness so that, if only for a brief moment or two, we feel that “intuition of some deeper, more ‘god-like’ state of satisfaction” in the throes of the orgasm. The sense of the forbidden, the prospect of something unknown and new tightens the mind, unifies our being and gives us a taste of what human consciousness should be like, but which we feel now only rarely, if at all. It is this unity of being that is the object of the sexual impulse. And as Wilson has pointed out in his many studies of the psychology of murder, some individuals so lack it that it is only in the most brutal acts of violence that they can feel some sense of it.

It is that tightening, that focus, that concentration, that is the source of the ‘god-like’ state of satisfaction – not the spice, whatever it may be. But the devotees of perversions – those with a jaded palate in need of heavily spiced food – do not grasp this, and rather than discipline themselves to achieve this focus through their own efforts, believe their “ultimate sexual satisfaction” will come through ratcheting up their intake of spices yet one more notch, oblivious to the law of diminishing returns inherent in the procedure. For just as a drug addict needs stronger and stronger doses of his poison in order to feel any effect, the sexually perverted – in the sense we are speaking of perversions – need greater and greater stimulants to “get it up.”

Yet achieving that focus through one’s own efforts, and not being reliant on the stimulus of the “forbidden,” would not only make sex more exciting, that is more real, but everything else too.

[1] The interested reader may wish to consult Herbert Spiegelberg’s classic The Phenomenological Movement (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1976). To get an idea of Wilson’s approach to phenomenology see Colin Wilson Introduction to the New Existentialism (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1967)

[2] See Origins of the Sexual Impulse (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1963), Order of Assassins: The Psychology of Murder (London: Rupert-Hart-Davis, 1972), and The Misfits: A Study of Sexual Outsiders (London: Grafton, 1988). Wilson has also used the novel as a means of exploring his ideas about sexuality: Ritual in the Dark (Kansas City, MO: Valancourt Books, 2020); Man Without a Shadow (Kansas City, MO: Valancourt Books, 2013; and The God of the Labyrinth (Kansas City, MO: Valancourt Books, 2013). For a summary of Wilson’s ideas about sex, see my Beyond the Robot: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson (New York: Tarcher Perigee, 2016) pp. 105-08.

[3] Colin Wilson Origins of the Sexual Impulse (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1963) p. 239.

[4] In the east it is a different matter, as the Christian missionaries who encountered religious sculptures depicting explicit sexual acts on Hindu temples discovered.

[5] Nicolai Berdyaev The Meaning of the Creative Act (New York: Collier’s, 1962) p. 168.

[6] From the procreation point of view, one could argue that any number of perversions would be acceptable and ‘normalised’ if in the end, sperm entered the womb and fertilised an egg. It would also seem to legitimise rape.

[7] Wilson 1963 p. 15.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid. p. 96.

[10] Ibid. P. 98.

[11] Ibid. pp. 147, 155, 247.