This review of Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary originally appeared in The LA Review of Books

Iain McGilchrist

The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World

Yale University Press, November 2010. 544 pp.

For millennia it’s been known that the human brain is divided into two hemispheres, the left and the right, yet exactly why has never been clear. What purpose this division served once seemed so obscure that the idea that one hemisphere was a “spare,” in case something went wrong with the other, was taken quite seriously. Yet the idea that the brain’s hemispheres, though linked, worked independently has a long history. As early as the third century B.C., Greek physicians speculated that the brain’s right hemisphere was geared toward “perception,” while the left was specialized in “understanding,” a rough and ready characterization that carries into our own time. In the 1970s and 1980s, the “split brain” became a hot topic in neuroscience, and soon popular wisdom produced a flood of books explaining how the left brain was a “scientist” and the right an “artist.”

Much insight into human psychology can be gleaned from these popular accounts, but “hard” science soon recognized that this simple dichotomy could not accommodate the wealth of data that ongoing research into hemispheric function produced. And as no “real” scientist wants to be associated with popular misconceptions — for fear of peer disapproval — the fact that ongoing research revealed no appreciable functionaldifferences between the hemispheres — they both seemed to “do” the same things, after all — made it justifiable for neuroscientists to put the split-brain question on the back burner, where it has pretty much stayed. Until now.

One popular myth about the divided brain that remained part of mainstream neuroscience was the perception of the left brain as “dominant” and the right as “minor,” a kind of helpful but not terribly important sidekick that tags along as the boss deals with the serious business. In his fascinating, groundbreaking, relentlessly researched, and eloquently written work, Iain McGilchrist, a consultant psychiatrist as well as professor of English — one wants to say a “scientist” as well as an “artist” — challenges this misconception. The difference between the hemispheres, McGilchrist argues, is not in what they do, but in how they do it. And it’s a difference that makes all the difference.

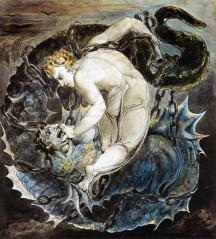

Although each hemisphere is involved in virtually everything the brain does, each has its own take on the world, or attitude toward it, we might say, that is radically opposed to that of the other half. For McGilchrist, the right hemisphere, far from minor, is fundamental — it is, as he calls it, “the Master” — and its task is to present reality as a unified whole. It gives us the big picture of a living, breathing “Other” — whatever it is that exists outside our minds — with which it is in a reciprocal relationship, bringing that Other into being (at least for our experience) while it is itself altered by the encounter. The left hemisphere, although not dominant as previously supposed, is geared toward manipulating that Other, on developing means of controlling it and fashioning it in its own likeness. We can say that the right side presents a world for us to live in, while the left gives us the means of surviving in it. Although both hemispheres are necessary to be fully alive and fully human (not merely fully “functioning”: a left brain notion), their different perspectives on the outside world often clash. It’s like looking through a microscope and at a panorama simultaneously. The right needs the left because its picture, while of the whole, is fuzzy and lacks precision. So it’s the job of the left brain, as “the Emissary,” to unpack the gestalt the right presents and then return it, increasing the quality and depth of that whole picture. The left needs the right because while it can focus on minute particulars, in doing so it loses touch with everything else and can easily find itself adrift. One gives context, the other details. One sees the forest, the other the trees.

It seems like a good combination, but what McGilchrist argues is that the hemispheres are actually in a kind of struggle or rivalry, a dynamic tension that, in its best moments (sadly rare), produces works of genius and a matchless zest for life, but in its worst (more common) leads to a dead, denatured, mechanistic world of bits and pieces, a collection of unconnected fragments with no hope of forming a whole. (The right, he tells us, is geared toward living things, while the left prefers the mechanical.) This rivalry is an expression of the fundamental asymmetry between the hemispheres.

Although McGilchrist’s research here into the latest developments in neuroimaging is breathtaking, the newcomer to neuroscience may find it daunting. That would be a shame. The Master and His Emissary, while demanding, is beautifully written and eminently quotable. For example: “the fundamental problem in explaining the experience of consciousness,” McGilchrist writes, “is that there is nothing else remotely like it to compare it with.” He apologizes for the length of the chapter dealing with the “hard” science necessary to dislodge the received opinion that the left hemisphere is the dominant partner, while the right is a tolerated hanger-on that adds a splash of color or some spice here and there. This formulation, McGilchrist argues, is a product of the very rivalry between the hemispheres that he takes pains to make clear.

McGilchrist asserts that throughout human history imbalances between the two hemispheres have driven our cultural and spiritual evolution. These imbalances have been evened out in a creative give-and-take he likens to Hegel’s dialectic, in which thesis and antithesis lead to a new synthesis that includes and transcends what went before. But what McGilchrist sees at work in the last few centuries is an increasing emphasis on the left hemisphere’s activities — at the expense of the right. Most mainstream neuroscience, he argues, is carried out under the aegis of scientific materialism: the belief that reality and everything in it can ultimately be “explained” in terms of little bits (atoms, molecules, genes, etc.) and their interactions. But materialism is itself a product of the left brain’s “take” on things (its tendency toward cutting up the whole into easily manipulated parts). It is not surprising, then, that materialist-minded neuroscientists would see the left as the boss and the right as second fiddle.

The hemispheres work, McGilchrist explains, by inhibiting each other in a kind of system of cerebral checks and balances. What has happened, at least since the Industrial Revolution (one of the major expressions of the left brain’s ability to master reality), is that the left brain has gained the upper hand in this inhibition and has been gradually silencing the right. In doing so, the left brain is in the process of re-creating the Other in its own image. More and more, McGilchrist argues, we find ourselves living in a world re-presented to us in terms the left brain demands. The danger is that, through a process of “positive feedback,” in which the world that the right brain “presences” is one that the left brain has already fashioned, we will find ourselves inhabiting a completely self-enclosed reality. Which is exactly what the left brain has in mind. McGilchrist provides disturbing evidence that such a world parallels that inhabited by schizophrenics.

¤

If nothing else, mainstream science’s refusal to accept that the whole can be anything more than the sum of its parts is one articulation of this development. The right brain, however, which knows better — the whole always comes before and is more than the parts, which are only segments of it, abstracted out by the left brain — cannot argue its case, for the simple reason that logical, sequential argument isn’t something it does. It can only show and provide the intuition that it is true. So we are left in the position of knowing that there is something more than the bits and pieces of reality the left brain gives us, but of not being able to say what it is — at least not in a way that the left brain will accept.

Poets, mystics, artists, even some philosophers (Ludwig Wittgenstein, for example, on whom McGilchrist draws frequently) can feel this, but they cannot provide the illusory certainty that the left brain requires: “illusory” because the precision such certainty requires is bought at the expense of knowledge of the whole. The situation is like thinking that you’re in love and having a scientist check your hormones to make sure. If he tells you that they’re not quite right, what are you going to believe: your fuzzy inarticulate feelings or his clinical report? Yet because the left brain demands certainty — remember, it focuses on minute particulars, nailing the piece down exactly by extracting it from the whole — it refuses to accept the vague sense of a reality larger than what it has under scrutiny as anything other than an illusion.

This may seem an interesting insight into how our brains operate, but we might ask what it really means for us. In a sense, all of McGilchrist’s meticulous marshalling of evidence is in preparation for this question, and while he is concerned about the left brain’s unwarranted eminence, he in no way suggests that we should jettison it and its work in favour of a cosy pseudo-mysticism. One of his central insights is that the kind of world we perceive depends on the kind of attention we direct toward it, a truth that phenomenologists like Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger — both invoked by McGilchrist — established long ago. In the homely maxim, to a man with a hammer everything looks like a nail. To the right brain, the world is — and, if we’re lucky, its “isness” produces in us a sense of wonder, something along the lines of a Zen satori or a sudden delight in the sheer interestingness of things. (As Heidegger and a handful of other thinkers said, that there should be anything rather than nothing is the inescapable mystery at the heart of things, a mystery that more analytical thinkers dismiss as nonsense.)

To the left brain, on the other hand, the world is something to be controlled, and understandably so, as in order to feel its “isness” we have to survive. McGilchrist argues that in a left-brain dominant world, the emphasis would be on increasing control, and the means of achieving this is by taking the right brain’s presencing of a whole and breaking it up into bits and pieces that can be easily reconstituted as a re-presentation, a symbolic virtual world, shot through with the left brain’s demand for clarity, precision, and certainty. Furthermore, McGilchrist contends that this is the kind of world we live in now, at least in the postmodern West. I find it hard to argue with his conclusion. What, for example, dotechnologies like HD and 3D do other than re-create a “reality” we prefer to absorb electronically?

McGilchrist contends that in pre-Socratic Greece, during the Renaissance, and throughout the Romantic movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the two hemispheres reached a brilliant accord, each augmenting the other’s contribution. Through their creative opposition (as William Blake said, “Opposition is True Friendship”) they produced a high culture that respected the limits of certainty and honored the implicit, the tacit, and the ambiguous (Keats’s “negative capability”). But since the Romantics, the left brain has increasingly gained more ground; our use of “romantic” as a pejorative term is itself a sign of this. With the rise of modernism and then postmodernism, the notion that there is anything outside our representations has become increasingly jejune, and what nature remains accessible to us is highly managed and resourced. McGilchrist fears that in the rivalry between its two halves, the left brain seems to have gained the upper hand and is steadily creating a hall of mirrors, which will soon reflect nothing but itself, if it doesn’t do so already.

The diagnosis is grim, but McGilchrist does leave some room for hope. After all, the idea that life is full of surprises is a right brain insight, and as the German poet Hölderlin understood, where there is danger, salvation lies also. In some Eastern cultures, especially Japan, where the right brain view of things still carries weight, McGilchrist sees some possibility of correcting our imbalance. But even if you don’t accept McGilchrist’s thesis, the book is a fascinating treasure trove of insights into language, music, society, love, and other fundamental human concerns. One of his most important suggestions is that the view of human life as ruthlessly driven by “selfish genes” and other “competitor” metaphors may be only a ploy of left brain propaganda, and through a right brain appreciation of the big picture, we may escape the remorseless push and shove of “necessity.” I leave it to the reader to discover just how important this insight is. Perhaps if enough do, we may not have to settle for what’s left when there’s no right.

¤

Gary Lachman is the author of more than a dozen books on the links between consciousness, culture, and the western counter-tradition, including Jung the Mystic, and A Secret History of Consciousness. He is a contributor to the Independent on Sunday, Fortean Times, and other journals in the US and UK, and lectures frequently on his work. A founding member of the pop group Blondie, as Gary Valentine he is the author of the memoir New York Rocker: My Life in the Blank Generation.http://bit.ly/vYVmpN